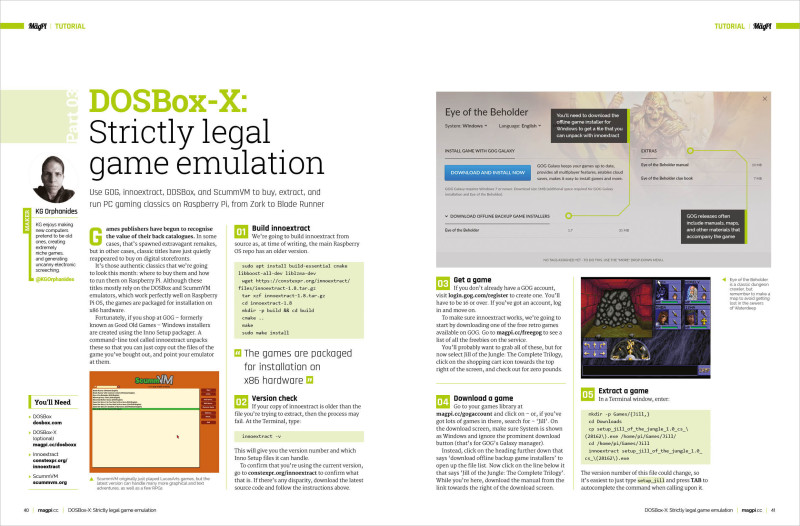

Reading Time: 6 minutesYou’ll need

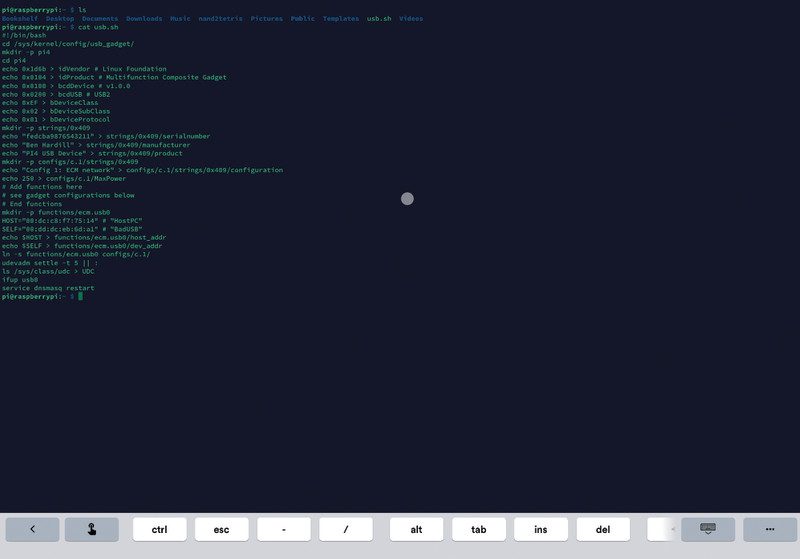

Build innoextract

We’re going to build innoextract from source as, at time of writing, the main Raspberry OS repo has an older version.

sudo apt install build-essential cmake libboost-all-dev liblzma-dev

wget https://constexpr.org/innoextract/files/innoextract-1.8.tar.gz

tar xzf innoextract-1.8.tar.gz

cd innoextract-1.8

mkdir -p build && cd build

cmake ..

make

sudo make install

Version check

If your copy of innoextract is older than the file you’re trying to extract, then the process may fail. At the Terminal, type:

innoextract -v

This will give you the version number and which Inno Setup files it can handle.

To confirm that you’re using the current version, go to the innoextract website to confirm what that is. If there’s any disparity, download the latest source code and follow the instructions above.

Get a game

If you don’t already have a GOG account, visit login.gog.com/register to create one. You’ll have to be 16 or over. If you’ve got an account, log in and move on.

To make sure innoextract works, we’re going to start by downloading one of the free retro games available on GOG. Go to GOG to see a list of all the freebies on the service.

You’ll probably want to grab all of these, but for now select Jill of the Jungle: The Complete Trilogy, click on the shopping cart icon towards the top right of the screen, and check out for zero pounds.

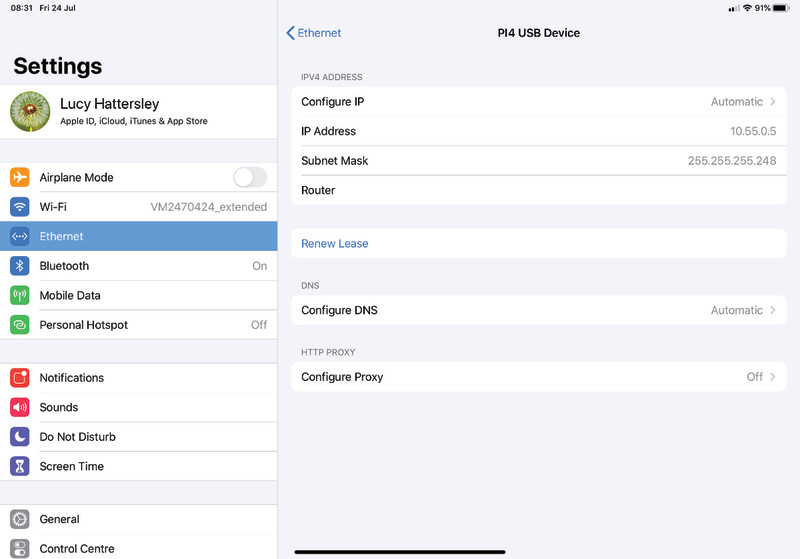

Download a game

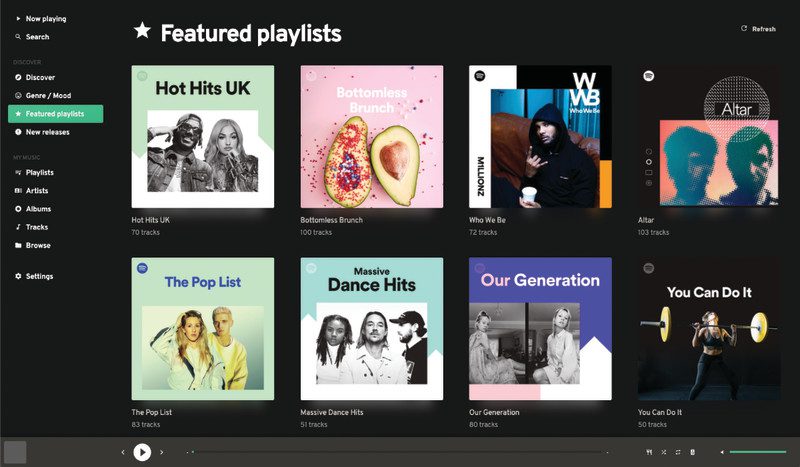

Go to your games library and click on – or, if you’ve got lots of games in there, search for – ‘Jill’. On the download screen, make sure System is shown as Windows and ignore the prominent download button (that’s for GOG’s Galaxy manager).

Instead, click on the heading further down that says ‘download offline backup game installers’ to open up the file list. Now click on the line below it that says ‘Jill of the Jungle: The Complete Trilogy’. While you’re here, download the manual from the link towards the right of the download screen.

Extract a game

In a Terminal window, enter:

mkdir -p Games/{Jill,}

cd Downloads

cp setup_jill_of_the_jungle_1.0_cs_\(28162\).exe /home/pi/Games/Jill/

cd /home/pi/Games/Jill

innoextract setup_jill_of_the_jungle_1.0_cs_\(28162\).exe

The version number of this file could change, so it’s easiest to just type setup_jill and press TAB to autocomplete the command when calling upon it.

Play a game

If you’ve not already installed DOSBox (or DOSBox-X) during one of our previous tutorials, you’ll need it for this, so:

apt install dosbox

Once your DOS emulator is installed, type:

dosbox jill1.exe

Jill of the Jungle is a classic platformer from an era when shareware ruled the genre on MS-DOS. If you have a USB controller plugged in, press C on the initial setup screen to configure it – it’s a bit easier to get used to than arrow keys if you’re a regular WASD user.

The extraction process is the same for any of GOG’s Inno Setup packaged games, which includes most of their DOS era titles. If you’re working with games for Windows 95 through ME, such as Diablo, then you may need to follow our Windows 98 emulation feature. However, many now work smoothly with the ScummVM emulator, which runs natively on Raspberry Pi OS.

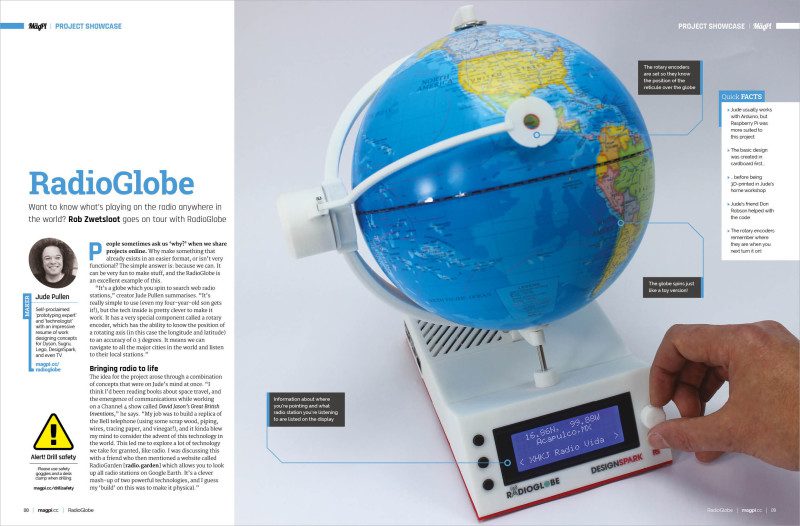

A hive of Scumm and villainy

If you want to play some games, rather than accurately emulating a full operating system, ScummVM, originally developed to play LucasArts point-and-click adventures such as The Secret of Monkey Island, is an outstanding tool with massive scope. Over the years, it’s expanded to emulate virtually every graphical adventure game out there, and the latest versions even support classic RPGs and text adventures.

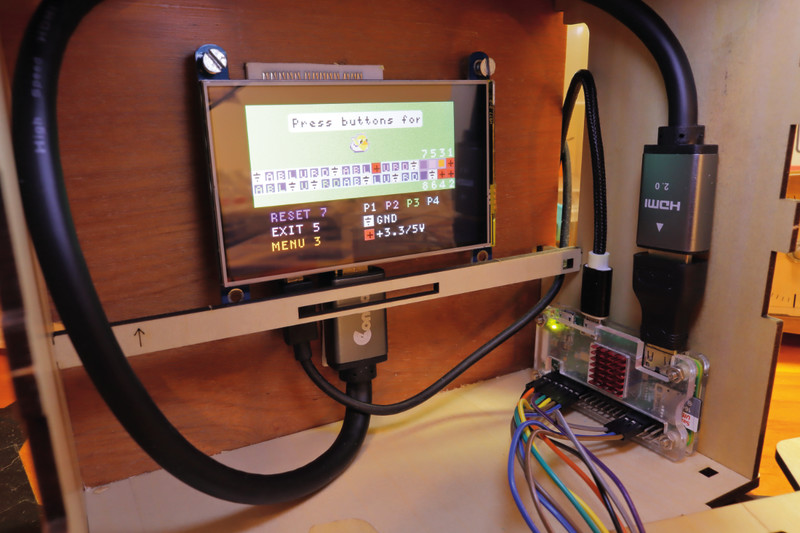

At the time of writing, ScummVM is at version 2.1.1, and we strongly recommend always using the latest version to ensure the widest possible support for newly added games. The current version available in Raspberry Pi OS’s repositories is 2.0.0, which lacks some of the cooler features of its successor.

So let’s head to the Terminal for a source install:

wget https://www.scummvm.org/frs/scummvm/2.1.1/scummvm-2.1.1.tar.gz

tar xzf scummvm-2.1.1.tar.gz

cd scummvm-2.1.1

apt install g++ make git libsdl2-dev liba52-dev libjpeg62-turbo-dev libmpeg2-4-dev libogg-dev libvorbis-dev libflac-dev libmad0-dev libpng-dev libtheora-dev libfaad-dev libfluidsynth-dev libfreetype6-dev zlib1g-dev libfribidi-dev libsdl2*

./configure

make clean

make -j4

make install

Even better for legal retronauts, you can find a range of classic games, re-released as freeware, to download at scummvm.org/games, including Revolution Software’s Beneath a Steel Sky and Lure of the Temptress, as well as other once-commercial releases like Creative Reality’s cyberpunk adventure DreamWeb and Interactive Binary Illusions’ Flight of the Amazon Queen. You’ll also find some of these in Raspberry Pi OS’s official repositories. If you want them, enter:

sudo apt install lure-of-the-temptress beneath-a-steel-sky drascula flight-of-the-amazon-queen

Just as re-releases of retro DOS games are frequently bundled with a functional copy of DOSBox, point-and-click re-releases often use ScummVM. When extracting files bought from GOG, you can delete or ignore the Windows version of the emulator that’s included and just point your own at the game files.

Games for free

Ensuring that your retro games are legally sourced can be a challenge online, but as well as digital storefronts, a number of free software sites are also committed to sharing only fully legit content, from shareware, homebrew, and demos to games made freeware by their publishers.

All vetted for licensing, you’ll find everything from shareware FPS classics to game makers and freeware re-releases. A well-supplied kids’ section and a violence warning system are handy for both parents and anyone who’s all Grimdarked out.

While there’s some replication between this and DOSGames, the inclusion of non-playable demos makes this archive an interesting stop for games history buffs.

People are still making games for DOS, and you can find almost 20 years’ worth of those homebrew projects here, from the outré to the winningly sincere.

Top tips

Remember to check that the game you want to play is supported by your emulator of choice. DOSBox and ScummVM publish lists of supported titles, and GOG store pages list the emulator they use at the very bottom.

Make sure the re-release includes any manuals, maps, and multimedia material you’ll need – some digital re-releases have been created with more care than others, and manual-based copy protection was common in the DOS era.

GOG isn’t the only place to buy retro games, but it has a wide range of titles and its installers are easy to extract. However, if you already own some classics on Steam, there’s generally no DRM on these, so you can simply copy their files over to Raspberry Pi.

Use the biggest microSD card you can. As games move into the full-speech era, you’ll find plenty that come in at around a gigabyte each.

‘Abandonware’ is a term used online for old software that players believe has been ‘abandoned’ by its rights holders. Although this scene has been important for games preservation, there’s no legal basis for abandonware in most countries, and downloading it is still software piracy. We stick to legal software.

‘Homebrew’, on the other hand, is new, independent, and generally non-commercial software made for traditionally closed or nominally defunct platforms. While homebrew titles can often be played on original hardware, they’re ideal for emulation. They’re generally fully legal, although some fan games have been known to appropriate graphical assets.

Three to buy

Loom | Price: £5

With a soundtrack and imagery inspired by Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, Brian Moriarty’s Loom is a beautifully woven adventure game with a compelling magical setting. The CD version has full speech, but there’s a bit more game to play if you opt for the EGA original.

Eye of the Beholder | Price: £8

A classic of the flick-screen dungeon crawling genre, Eye of the Beholder is one of the most approachable Advanced Dungeons & Dragons RPGs and oozes atmosphere. Perhaps unexpectedly, it works perfectly through ScummVM, making for a particularly easy emulation experience. Both its sequels are included in the bundle.

Blade Runner | Price: £8

As dark and gritty as Blade Runner’s cinematic universe, and features some of the cast from Ridley Scott’s 1982 film, the Blade Runner adventure game was for years effectively lost to licensing disputes and lack of format support until it appeared in GOG’s catalogue in 2019. It’s a unique and much-lauded work that contributes to the series’ mythos in its own right, but carries content warnings off the bat for extremely mature subject matter.