Schlagwort: The MagPi

-

Humane mouse trap | The MagPi #108

Reading Time: 4 minutesSafely catching mice is a better way of fixing a problem, and using Raspberry Pi means it needs less supervision. In the new issue of The MagPi magazine, Rob Zwetsloot takes a look with the maker, Andrew Taylor. With some IoT projects, it’s the little things that help. For example, take Andrew…

-

Get outside with these Raspberry Pi summer projects

Reading Time: 5 minutesSummer is fast approaching – and that’s the perfect excuse to get building. Whether you want to spy on your local wildlife, upgrade your vegetable patch, or feed your fish when you’re off on a weekend break, Raspberry Pi and a handful of add-ons make a great starting point. The latest issue…

-

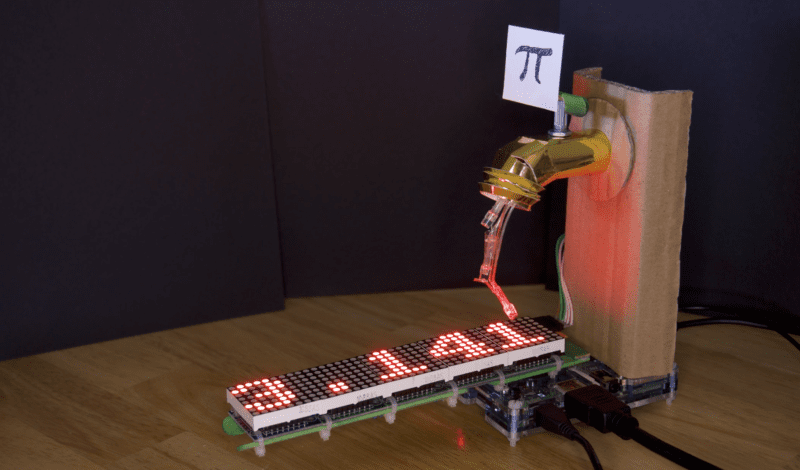

Calculate pi with a Raspberry Pi Spigot | The MagPi #106

Reading Time: 4 minutesHere’s an ingenious way of using a Raspberry Pi to calculate pi – and why not? Nicola King runs the numbers in the latest issue of The MagPi magazine. Pi is an irrational number, which means it can’t be expressed as the ratio of two integers. Since it has an infinite number of…

-

Meet Ellora James

Reading Time: 4 minutesIn the latest issue of The MagPi magazine, we meet the smart young computer scientist behind an exciting new YouTube channel. When did you have that ‘ah-hah’ moment with computing? Ellora James remembers when she had hers. “When I was about 14/15 years old, I was considering taking Computer Science at exam…

-

Star Wars Arcade Cabinet | The MagPi #105

Reading Time: 4 minutesWhy pay over the odds when you can build an accurate replica, and have fun doing it? For the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine, Rob Zwetsloot switches off his targeting computer to have a look. Art had to be rescaled, but it’s been done faithfully Getting the arcade machine of your…

-

Raspberry Pi Zero W turns iPod Classic into Spotify music player

Reading Time: 4 minutesRecreating Apple’s iconic iPod Classic as a Spotify player may seem like sacrilege but it works surprisingly well, finds Rosie Hattersley. Check out the latest issue of The MagPi magazine (pg 8 – 12) for a tutorial to follow if you’d like to create your own. Replacement Raspberry Pi parts laying inside…

-

Kay-Berlin Food Computer | The MagPi #104

Reading Time: 4 minutesIn the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine, out today, Rob Zwetsloot talks to teacher Chris Regini about the incredible project his students are working on. When we think of garden automation, we often think of basic measures like checking soil moisture and temperature. The Kay-Berlin Food Computer, named after student creators…

-

#MonthOfMaking is back in The MagPi 103!

Reading Time: 3 minutesHey folks, Rob from The MagPi here! I hope you’ve been doing well. Despite how it feels, a brand-new March is just around the corner. Here at The MagPi, we like to celebrate March with our annual #MonthOfMaking event, where we want to motivate you to get making. You could make tech…

-

Raspberry Pi engineers on the making of Raspberry Pi Pico | The MagPi 102

Reading Time: 4 minutesIn the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine, on sale now, Gareth Halfacree asks what goes into making Raspberry Pi’s first in-house microcontroller and development board. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o-tRJPCv0GA?feature=oembed&w=500&h=281] “It’s a flexible product and platform,” says Nick Francis, Senior Engineering Manager at Raspberry Pi, when discussing the work the Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC)…

-

The Stargate | The MagPi 101

Reading Time: 4 minutesFans of the Stargate SG-1 series, prepare to be inspired: a fellow aficionado has fashioned his own model of the show’s iconic portal. Nicola King takes an interstellar trip in the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine. When Kristian Tysse began making some projects on his new 3D printer, he soon became…

-

100 Raspberry Pi moments

Reading Time: 4 minutesThe official Raspberry Pi magazine turned 100 this month! To celebrate, the greatest Raspberry Pi moments, achievements, and events that The MagPi magazine has ever featured came back for a special 100th issue. 100 Raspberry Pi Moments is a cracking bumper feature (starting on page 32 of issue 100, if you’d like…

-

The MagPi #100: celebrate 100 amazing moments from Raspberry Pi history

Reading Time: 3 minutesHey there, folks, Rob from The MagPi here! I hope you’ve all been doing OK. Today we celebrate the 100th issue of The MagPi, the official Raspberry Pi magazine! Most of you probably know that The MagPi didn’t start off official, though: eight and a half years ago, intrepid community members came…

-

Mars Clock

Reading Time: 4 minutesA sci-fi writer wanted to add some realism to his fiction. The result: a Raspberry Pi-based Martian timepiece. Rosie Hattersley clocks in from the latest issue of The MagPi Magazine. The Mars Clock project is adapted from code Phil wrote in JavaScript and a Windows environment for Raspberry Pi Ever since he…

-

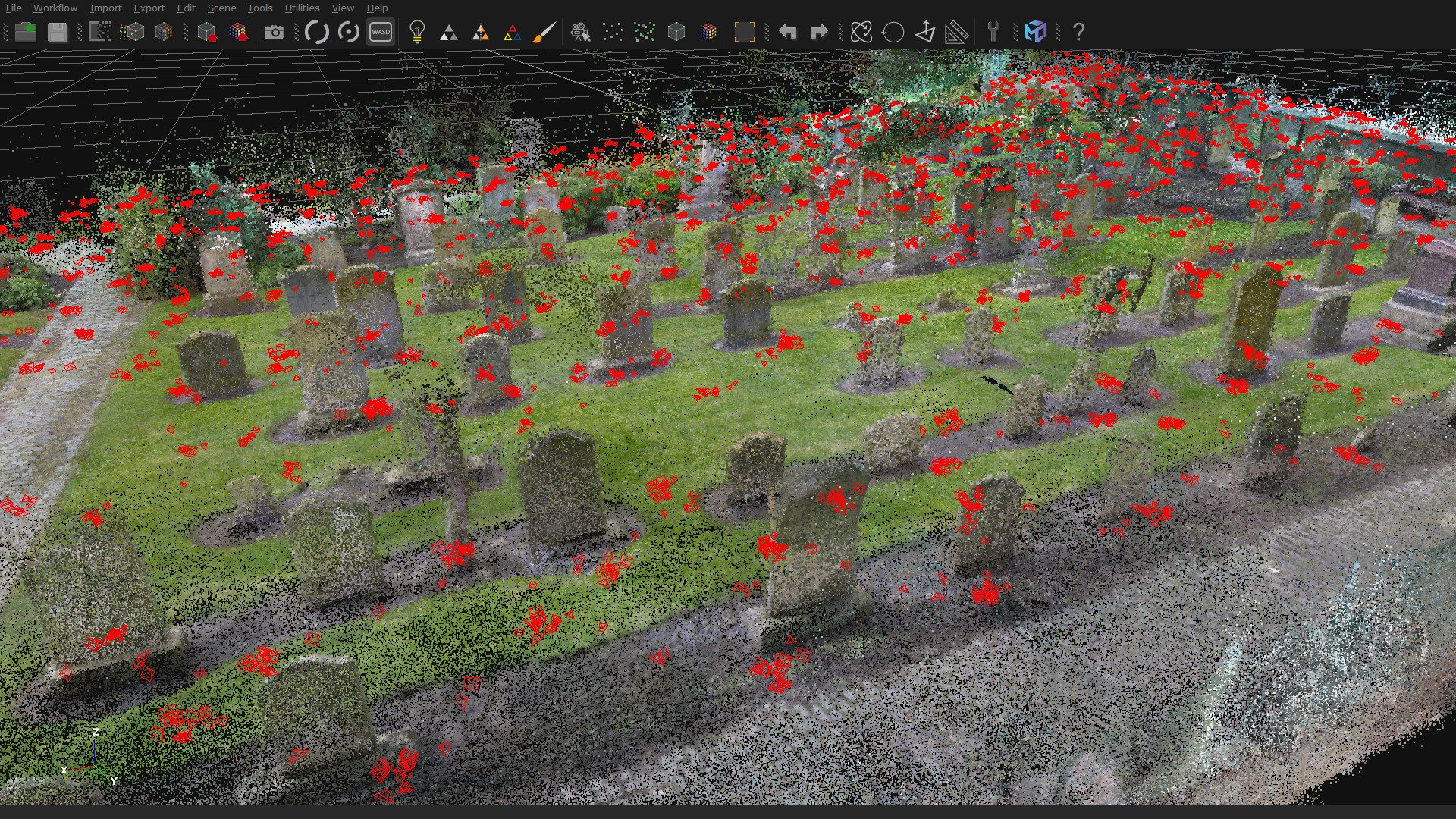

The Howff 3D scanning rig| The MagPi 99

Reading Time: 4 minutesHow do you create a 3D model of a historic graveyard? With eight Raspberry Pi computers, as Rob Zwetsloot discovers in the latest issue of The MagPi magazine, out now. The software builds up the 3D model of the graveyard “In the city centre of Dundee is a historical burial ground, The…

-

(Raspberry) Pi Commander | The MagPi 95

Reading Time: 4 minutesAdrien Castel’s idea of converting an old electronic toy into a retro games machine was no flight of fancy, as David Crookes discovers The 1980s was a golden era for imaginative electronic toys. Children would pester their parents for a Tomytronic 3D or a Nintendo Game & Watch. And they would enviously…

-

Monitoring bees with a Raspberry Pi and BeeMonitor

Reading Time: 4 minutesKeeping an eye on bee life cycles is a brilliant example of how Raspberry Pi sensors help us understand the world around us, says Rosie Hattersley The setup featuring an Arduino, RF receiver, USB cable and Raspberry Pi Getting to design and build things for a living sounds like a dream job,…

-

The Raspberry Pi Press store is looking mighty fine

Reading Time: 3 minutesEagle-eyed Raspberry Pi Press fans might have noticed some changes over the past few months to the look and feel of our website. Today we’re pleased to unveil a new look for the Raspberry Pi Press website and its online store. Did you know? Raspberry Pi Press is the publishing imprint of…

-

Special offer for magazine readers

Reading Time: 2 minutesYou don’t need me to tell you about the unprecedented situation that the world is facing at the moment. We’re all in the same boat, so I won’t say anything about it other than I hope you stay safe and take care of yourself and your loved ones. The other thing I…

-

Instaclock | The Magpi 92

Reading Time: 4 minutesDesigned to celebrate a new home, Instaclock uses two Raspberry Pi computers to great visual effect. Rosie Hattersley introduces maker Riccardo Cereser’s eyecatching build in issue #92 of The MagPi, out now. There is nothing like a deadline to focus the mind! Copenhagen-based illustrator and UX designer Riccardo Cereser was about to…

-

El Carrillon | The MagPi 92

Reading Time: 3 minutesMost Raspberry Pi projects we feature debut privately and with little fanfare – at least until they’re shared by us. The El Carrillon project, however, could hardly have made a more public entrance. In September 2019 it was a focal point of Argentina’s 49th annual Fiesta Nacional de la Flor (National Flower…

-

The MagPi 91: #MonthOfMaking is back for 2020!

Reading Time: 4 minutesIf you read The MagPi, it’s safe to say you like making in some way. The hobby has exploded in popularity over the last few years, thanks in no small part to a burgeoning online community and the introduction of low-cost computing with Raspberry Pi. Last year we decided to celebrate making…