A monumental make

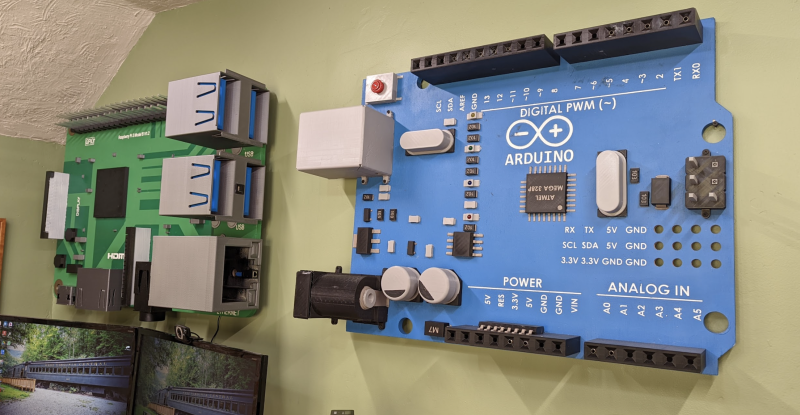

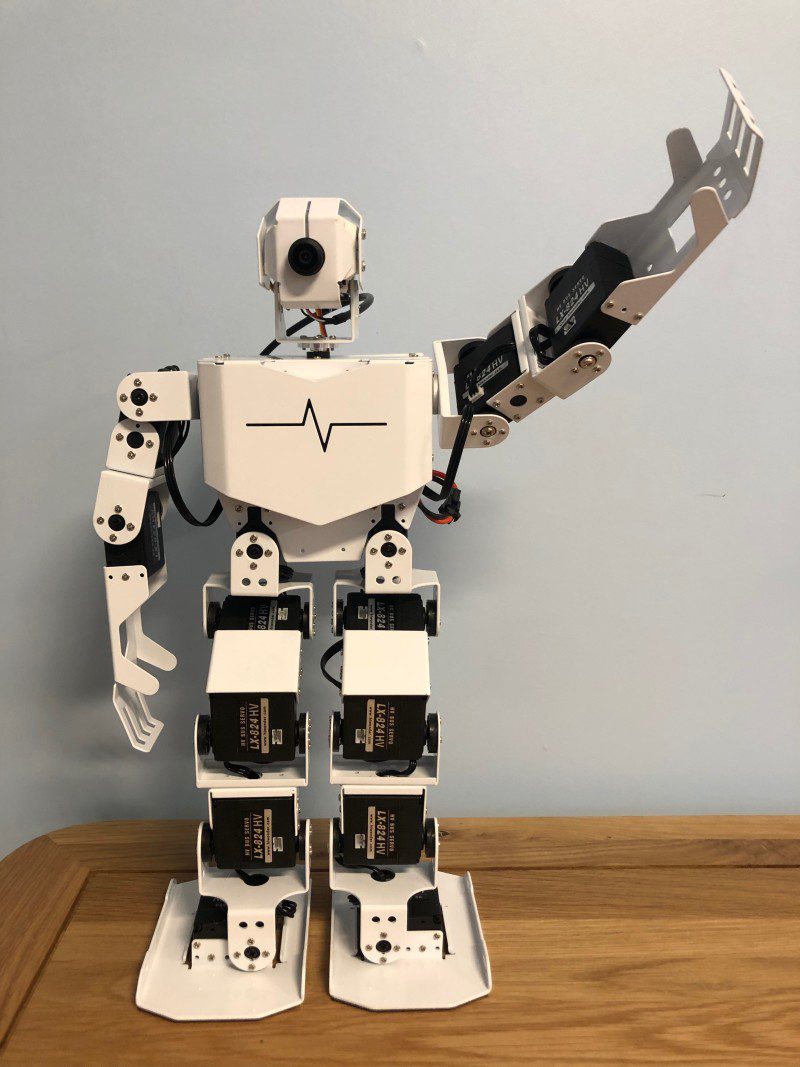

“I have always loved working with microcontrollers and single-board computers,” Zach tells us. “At the end of 2020 I built a large-scale Arduino board and posted a video about it on my YouTube channel. I had lots of suggestions and requests that I build large-scale versions of other DIY electronics components. It wasn’t a far stretch for me to want to do another similar project, and that’s where the giant Raspberry Pi board was born.”

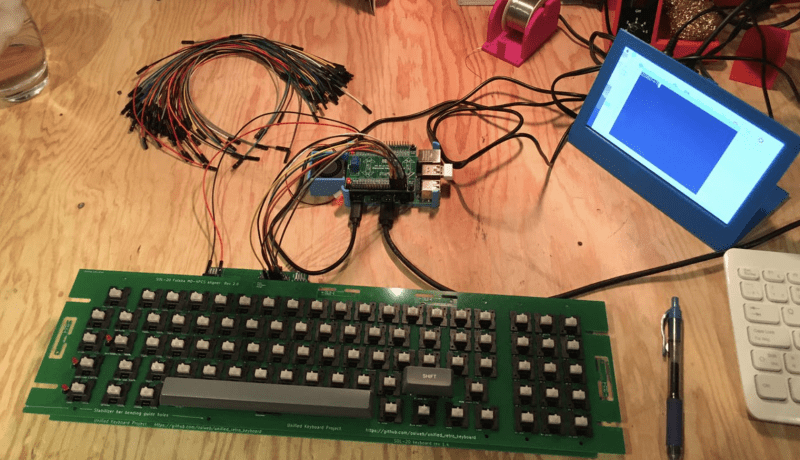

Zach says he learnt a great deal from his first giant project build and used his knowledge from that in the latest construction. “The most time-consuming part was printing the large-scale components, which took over 150 hours to complete. I used over 5 kg of PLA filament on this project alone,” he reveals.

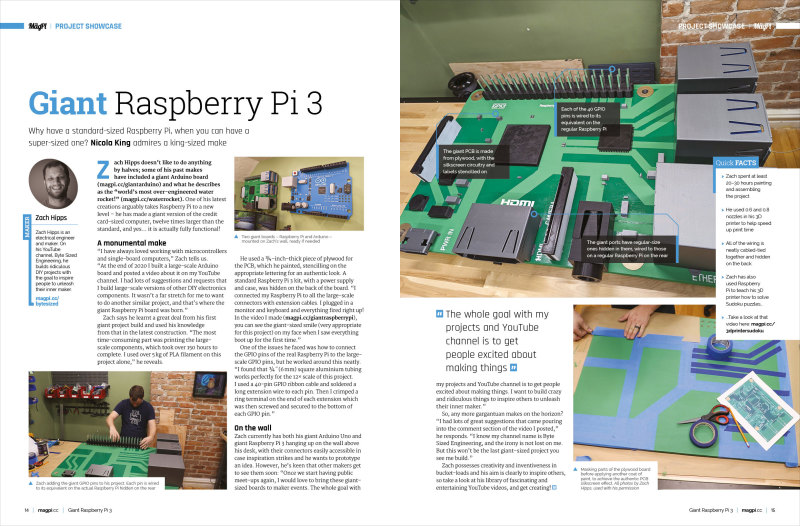

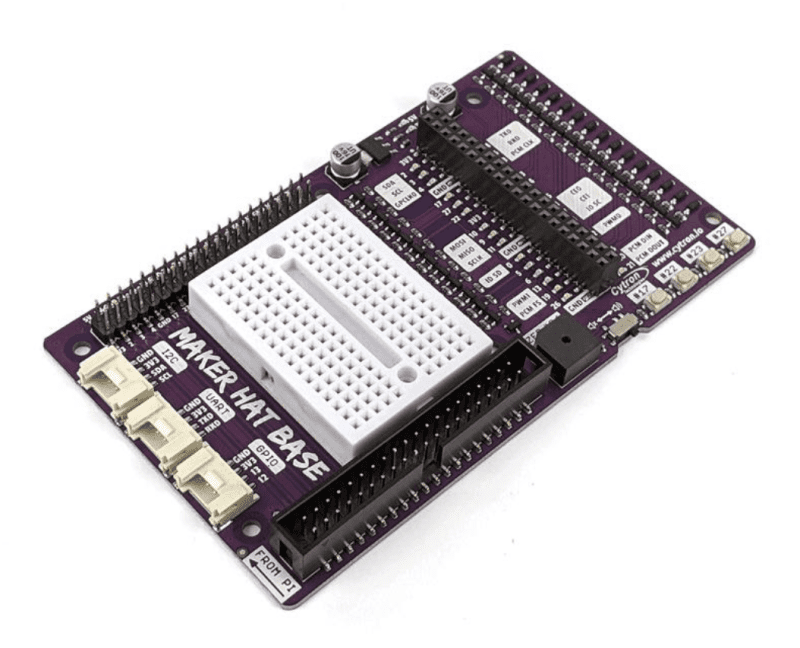

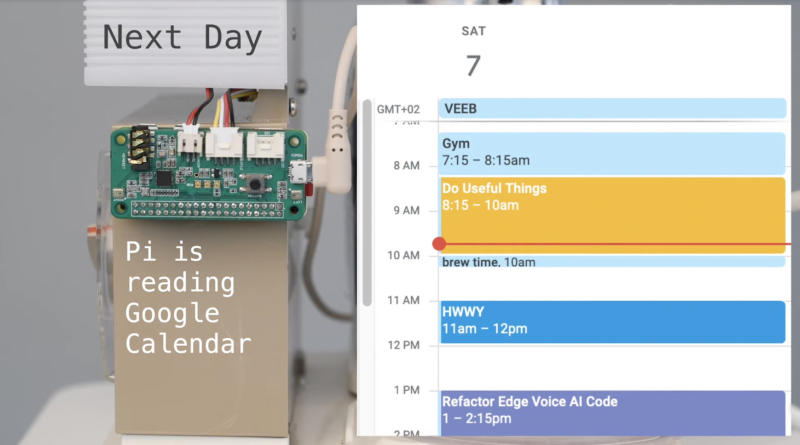

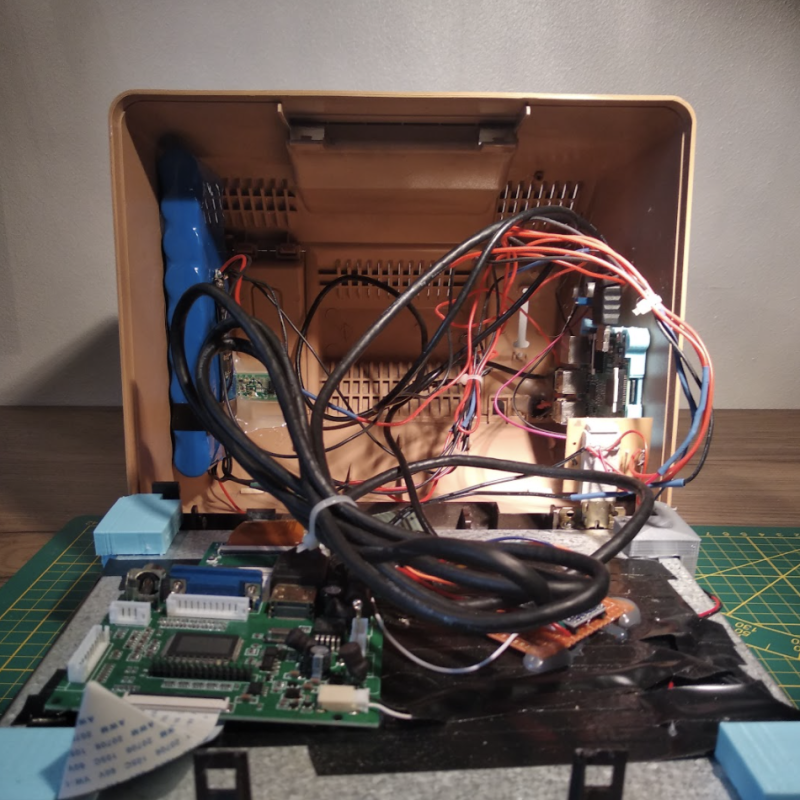

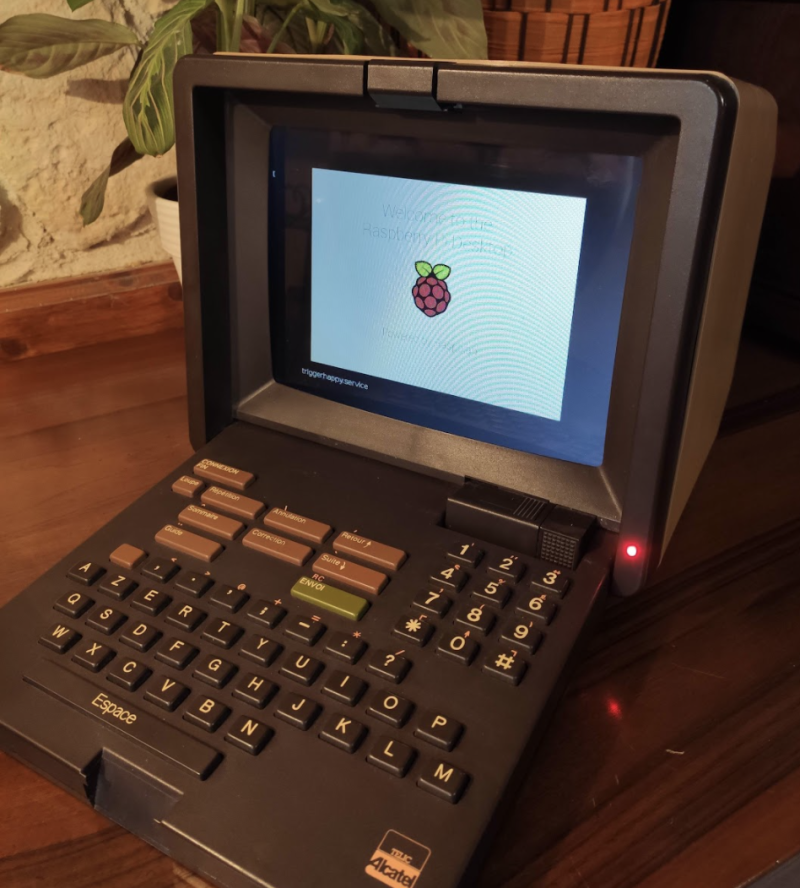

He used a ¾-inch-thick piece of plywood for the PCB, which he painted, stencilling on the appropriate lettering for an authentic look. A standard Raspberry Pi 3 kit, with a power supply and case, was hidden on the back of the board. “I connected my Raspberry Pi to all the large-scale connectors with extension cables. I plugged in a monitor and keyboard and everything fired right up! In the video I made, you can see the giant-sized smile (very appropriate for this project) on my face when I saw everything boot up for the first time.”

One of the issues he faced was how to connect the GPIO pins of the real Raspberry Pi to the large-scale GPIO pins, but he worked around this neatly. “I found that ¼˝ (6 mm) square aluminium tubing works perfectly for the 12× scale of this project. I used a 40-pin GPIO ribbon cable and soldered a long extension wire to each pin. Then I crimped a ring terminal on the end of each extension which was then screwed and secured to the bottom of each GPIO pin.”

On the wall

Zach currently has both his giant Arduino Uno and giant Raspberry Pi 3 hanging up on the wall above his desk, with their connectors easily accessible in case inspiration strikes and he wants to prototype an idea. However, he’s keen that other makers get to see them soon: “Once we start having public meet-ups again, I would love to bring these giant-sized boards to maker events. The whole goal with my projects and YouTube channel is to get people excited about making things. I want to build crazy and ridiculous things to inspire others to unleash their inner maker.”

So, any more gargantuan makes on the horizon? “I had lots of great suggestions that came pouring into the comment section of the video I posted,” he responds. “I know my channel name is Byte Sized Engineering, and the irony is not lost on me. But this won’t be the last giant-sized project you see me build.”

Zach possesses creativity and inventiveness in bucket-loads and his aim is clearly to inspire others, so take a look at his library of fascinating and entertaining YouTube videos, and get creating.