From May to November 2022, our seminars focus on the theme of cross-disciplinary computing. Through this seminar series, we want to explore the intersections and interactions of computing with all aspects of learning and life, and think about how they can help us teach young people. We were delighted to welcome Prof. Mark Guzdial (University of Michigan) as our first speaker.

Mark has worked in computer science (CS) education for decades and won many awards for his research, including the prestigious ACM SIGCSE Outstanding Contribution to Computing Education award in 2019. He has written literally hundreds of papers about CS education, and he authors an extremely popular computing education research blog that keeps us all up to date with what is going on in the field.

In his talk, Mark focused on his recent work around developing task-specific programming (TSP) languages, with which teachers can add a teaspoon (also abbreviated TSP) of programming to a wide variety of subject areas in schools. Mark’s overarching thesis is that if we want everyone to have some exposure to CS, then we need to integrate it into a range of subjects across the school curriculum. And he explained that this idea of “adding a teaspoon” embraces some core principles; for TSP languages to be successful, they need to:

- Meet the teachers’ needs

- Be relevant to the context or lesson in which it appears

- Be technically easy to get to grips with

Mark neatly summarised this as ‘being both usable and useful’.

Historical views on why we should all learn computer science

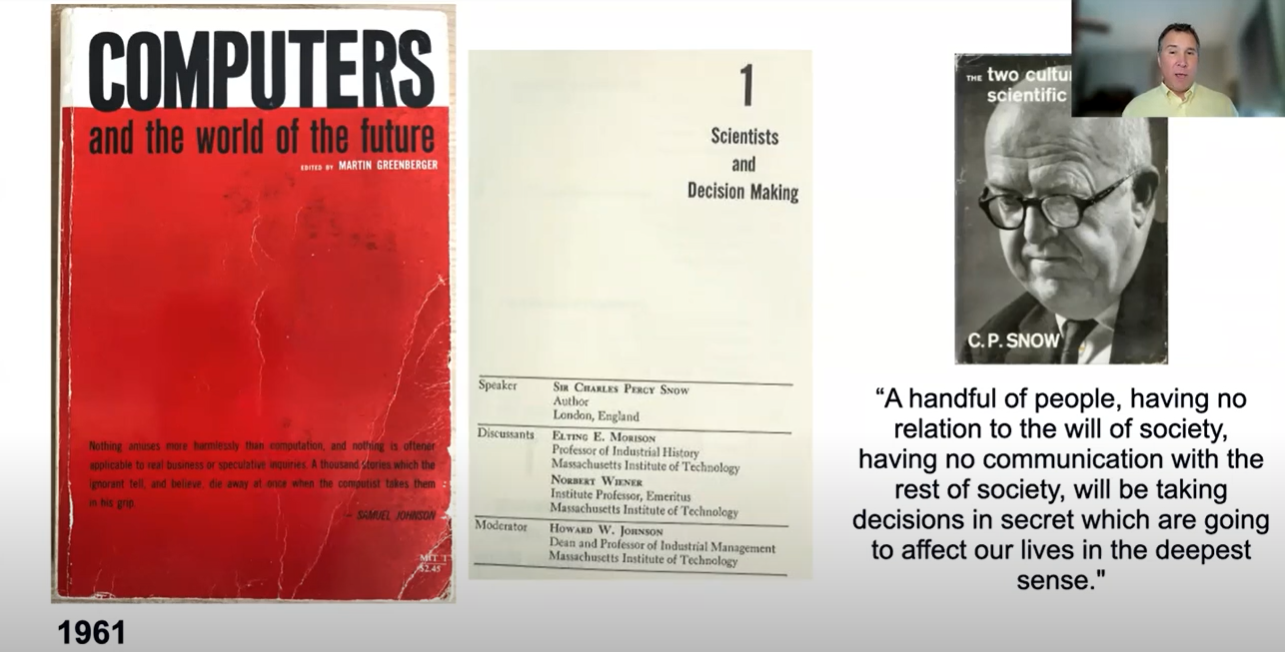

We can learn a lot from going back in time and reflecting on the history of computing. Mark started his talk by sharing the views of some of the eminent computer scientists of the early days of the subject. C. P. Snow maintained, way back in 1961, that all students should study CS, because it was too important to be left to a small handful of people.

Alan Perlis, also in 1961, argued that everyone at university should study one course in CS rather than a topic such as calculus. His reason was that CS is about process, and thus gives students tools that they can use to change the world around them. I’d never heard of this work from the 1960s before, and it suggests incredible foresight. Perhaps we don’t need to even have the debate of whether computer science is for everyone — it seems it always was!

What’s the problem with the current situation?

In many of our seminars over the last two years, we have heard about the need to broaden participation in computing in school. Although in England, computing is mandatory for ages 5 to 16 (in theory, in practice it’s offered to all children from age 5 to 14), other countries don’t have any computing for younger children. And once computing becomes optional, numbers drop, wherever you are.

Mark shared with us that in US high schools, only 4.7% of students are enrolled in a CS course. However, students are studying other subjects, which brought him to the conclusion that CS should be introduced where the students already are. For example, Mark described that, at the Advanced Placement (AP) level in the US, many more students choose to take history than CS (399,000 vs 114,000) and the History AP cohort has more even gender balance, and a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic students.

The teaspoon approach to broadening participation

A solution to low uptake of CS being proposed by Mark and his colleagues is to add a little computing to other subjects, and in his talk he gave us some examples from history and mathematics, both subjects taken by a high proportion of US students. His focus is on high school, meaning learners aged 14 and upwards (upper secondary in Europe, or key stage 4 and 5 in England). To introduce a teaspoon of CS to other subjects, Mark’s research group builds tools using a participatory design approach; his group collaborates with teachers in schools to identify the needs of the teachers and students and design and iterate TSP languages in conjunction with them.

Mark demonstrated a number of TSP language prototypes his group has been building for use in particular contexts. The prototypes seem like simple apps, but can be classified as languages because they specify a process for a computational agent to execute. These small languages are designed to be used at a specific point in the lesson and should be learnable in ten minutes. For example, students can use a small ‘app’ specific to their topic, look at a script that generates a visualisation, and change some variables to find out how they impact the output. Students may also be able to access some program code, edit it, and see the impact of their edits. In this way, they discover through practical examples the way computer programs work, and how they can use CS principles to help build an understanding of the subject area they are currently studying. If the language is never used again, the learning cost was low enough that it was worth the value of adding computation to the one lesson.

We have recorded the seminar and will be sharing the video very soon, so bookmark this page.

Try TSP languages yourself

You can try out the TSP language prototypes Mark shared yourself, which will give you a good idea of how much a teaspoon is!

DV4L: For history students, the team and participating teachers have created a prototype called DV4L, which visualises historical data. The default example script shows population growth in Africa. Students can change some of the variables in the script to explore data related to other countries and other historical periods. A example lesson activity illustrates how a teacher might incorporate this TSP language into a lesson.

Pixel Equations: Mathematics and engineering students can use the Pixel Equations tool to learn about the way that pictures are made up of individual pixels. This can be introduced into lessons using a variety of contexts. One example lesson activity looks at images in the contexts of maps. This prototype is available in English and Spanish.

Counting Sheets: Another example given by Mark was Counting Sheets, an interactive tool to support the exploration of counting problems, such as how many possible patterns can come from flipping three coins.

Have a go yourself. What subjects could you imagine adding a teaspoon of computing to?

Join our next free research seminar

We’d love you to join us for the next seminar in our series on cross-disciplinary computing. On 7 June, we will hear from Pratim Sengupta, of the University of Calgary, Canada. He has conducted studies in science classrooms and non-formal learning environments, focusing on providing open and engaging experiences for anyone to explore code. Pratim will share his thoughts on the ways that more of us can become involved with code when we open up its richness and depth to a wider audience. He will also introduce us to his ideas about countering technocentrism, a key focus of his new book.

And finally… save another date!

We will shortly be sharing details about the official in-person launch event of the Raspberry Pi Computing Education Research Centre at the University of Cambridge on 20 July 2022. And guess who is going to be coming to Cambridge, UK, from Michigan to officially cut the ribbon for us? That’s right, Mark Guzdial. More information coming soon on how you can sign up to join us for free at this launch event.

Website: LINK