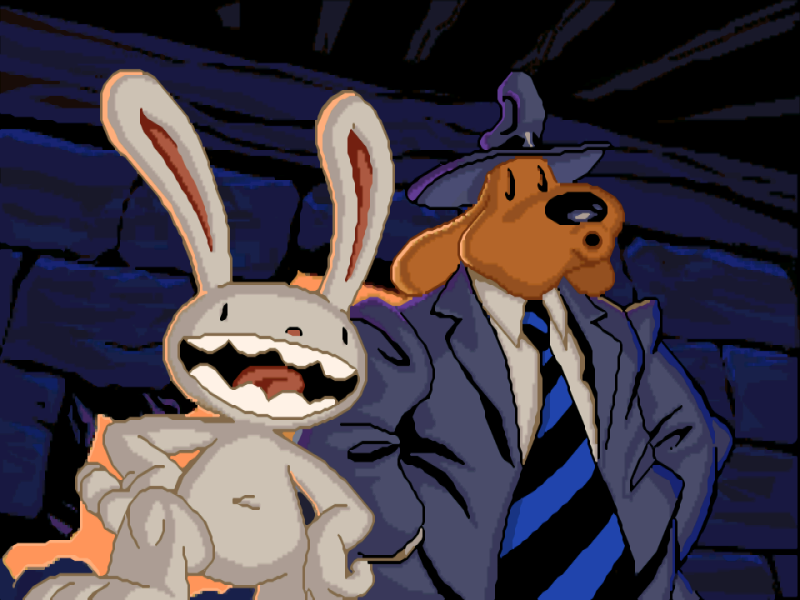

In this tutorial we’re going to look at a much broader range of legal console ROMs. Some can be purchased legally, while others have been developed and are distributed for free.

So let’s set up a RetroPie console and play some classic games.

Thriving scene

Sega’s Mega Drive Classics collections include ROM images of the games that you run on any emulator you like, and brand new commercial releases for Sega and other platforms are thriving, as are active homebrew scenes bringing innovative new games to console formats that went out of production over 25 years ago.

Sega is incredibly supportive of its emulation community, and is happy to just sell you some classic Mega Drive ROMs, included in the Sega Mega Drive Classics collections for Windows, macOS, and Linux. You can buy 50 classic Mega Drive games on Steam, either individually or as a pack.

Once bought, to find the ROMs, open the title’s Steam Library page, clear the gear icon on the right, select properties Properties, select the Local files tab, and then click Browse local files. You’ll find all the ROMs in the clearly labelled uncompressed ROMs directory. Rename all files with ‘.68K’ and ‘.SGD’ extensions to ‘.bin’ and copy them over to Raspberry Pi using a USB stick or via its Samba share.

Buy new classics

If you’re after new games for classic systems, itch.io should be your first port of call. The Nintendo Entertainment System is the most popular 8-bit console for modern developers, while the Mega Drive has won the hearts of 16-bit devs. Games are also available for the 8-bit Sega Master System and 16-bit Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

We’ve made itch.io collections for each of those platforms, going out of our way to avoid unauthorised ports and ROM hacks. These include both commercial and freeware games, plus a couple of open-source titles:

That’s not the only place that you’ll find releases for those platforms. In the tutorial, we download Mystery World Dizzy by the Oliver Twins. It’s a wonderful example of a lost NES game that was recovered by its creators and released as freeware to the fan community, but it’s also rare to find Nintendo games from that era re-released with their creators’ blessing. And unlike Sega, Nintendo doesn’t look fondly on ROM hacks, fan games, and the like.

On the homebrew side of things, projects such as Retrobrews and sites like vintageisthenewold.com and indieretronews.com compile collections and lists of homemade games for classic consoles, but watch out for the odd unauthorised port slipping into their catalogues.

There’s a small but lively industry releasing cartridges for retro consoles, and a number of developers and publishers make the ROM files available online, either for free or a small price. Among these are RetroSouls, the team behind Old Towers, and Miniplanets publisher Playonretro.

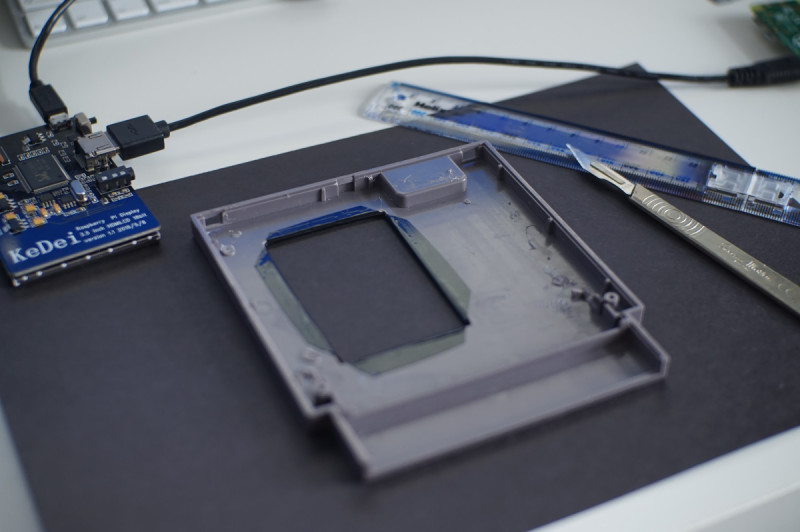

Image your RetroPie drive

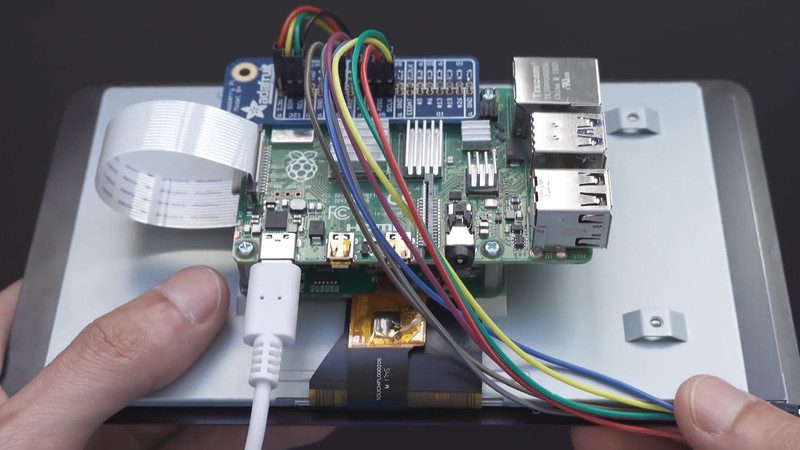

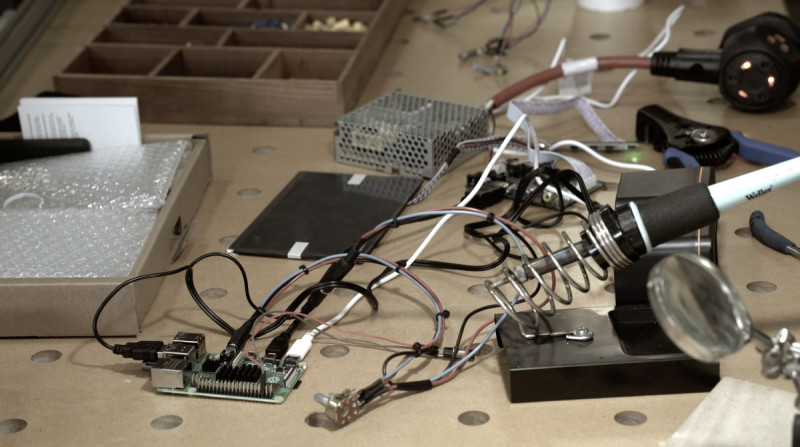

Download the Raspberry Pi Imager for your operating system. Insert a microSD card – 8GB will be fine if you plan to limit yourself to 8- and 16-bit games, but if you want to emulate more powerful consoles in future, a 32GB card is a good investment.

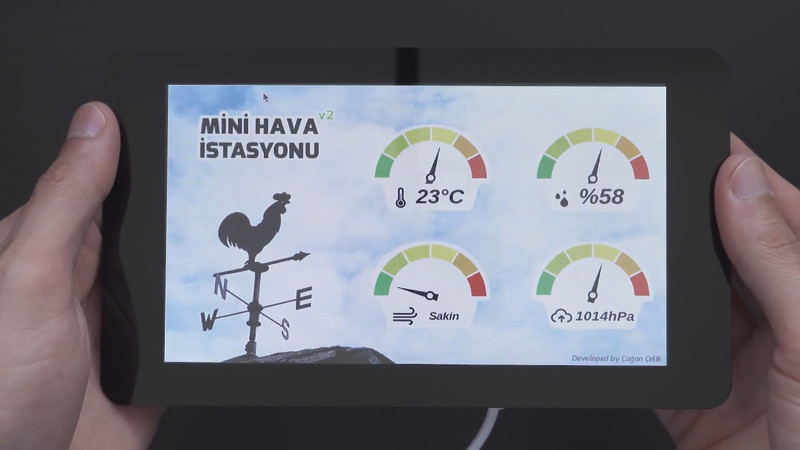

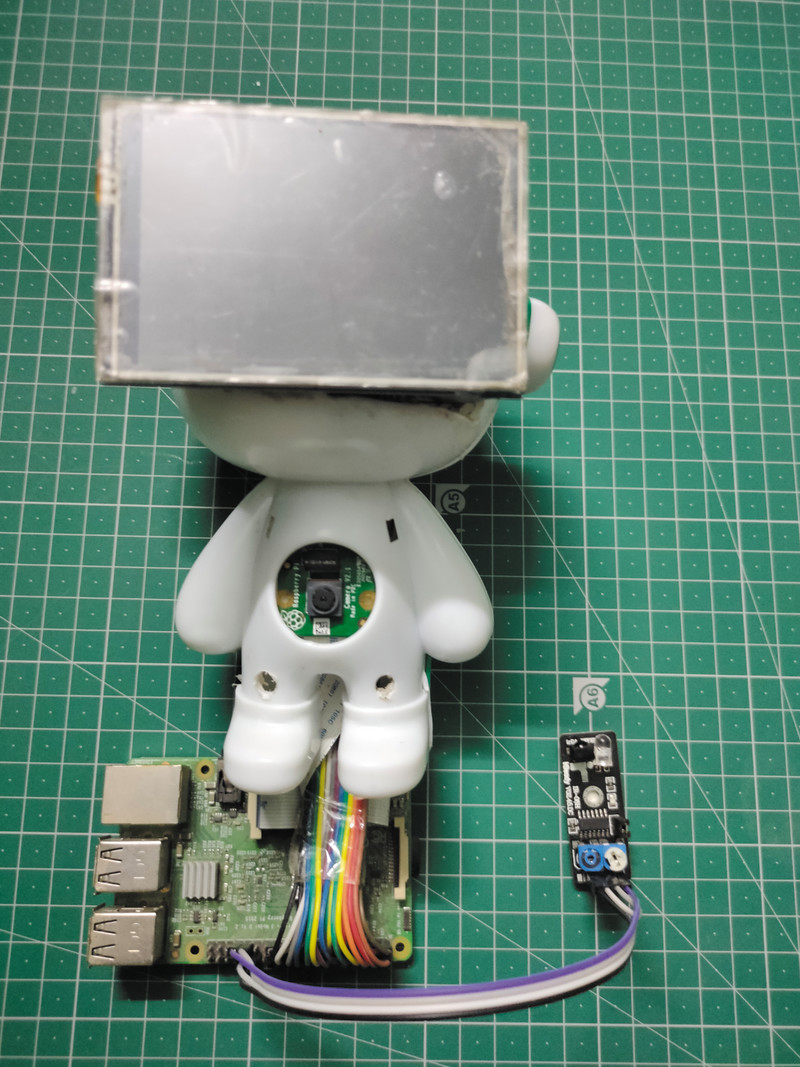

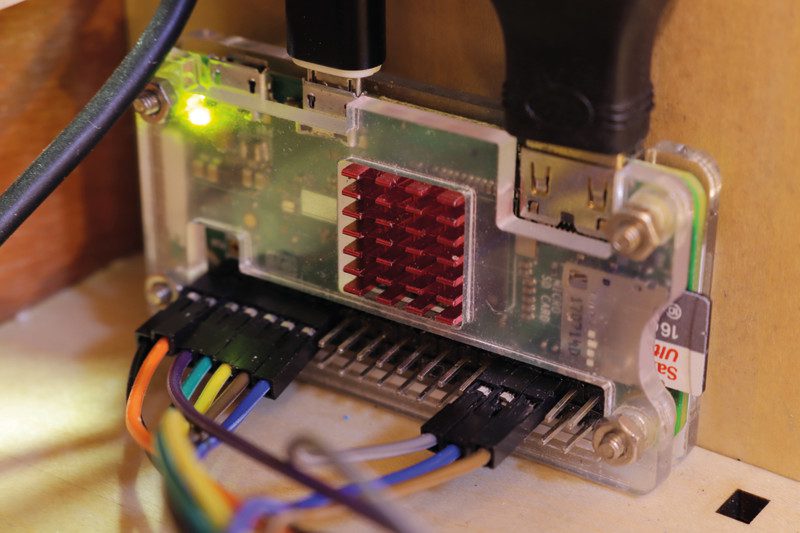

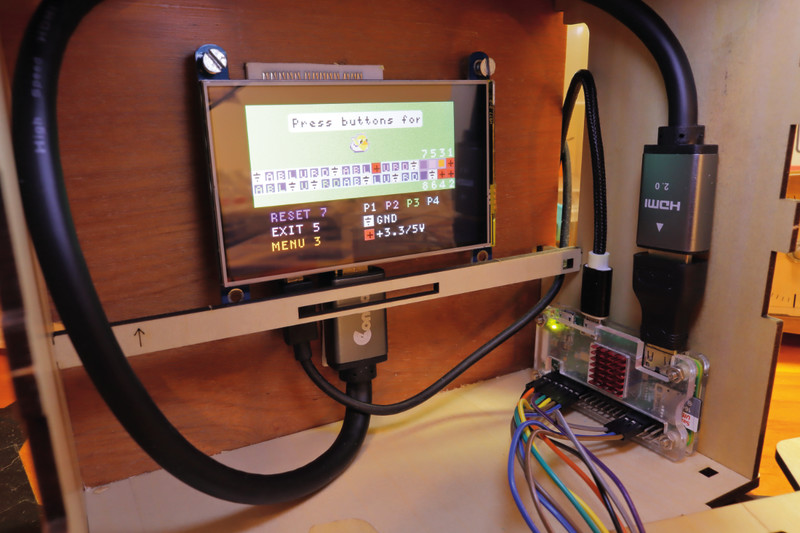

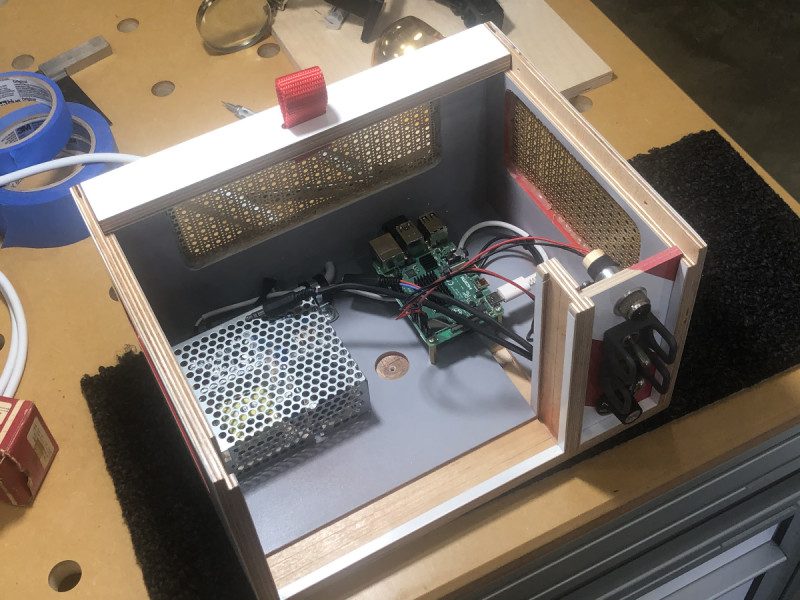

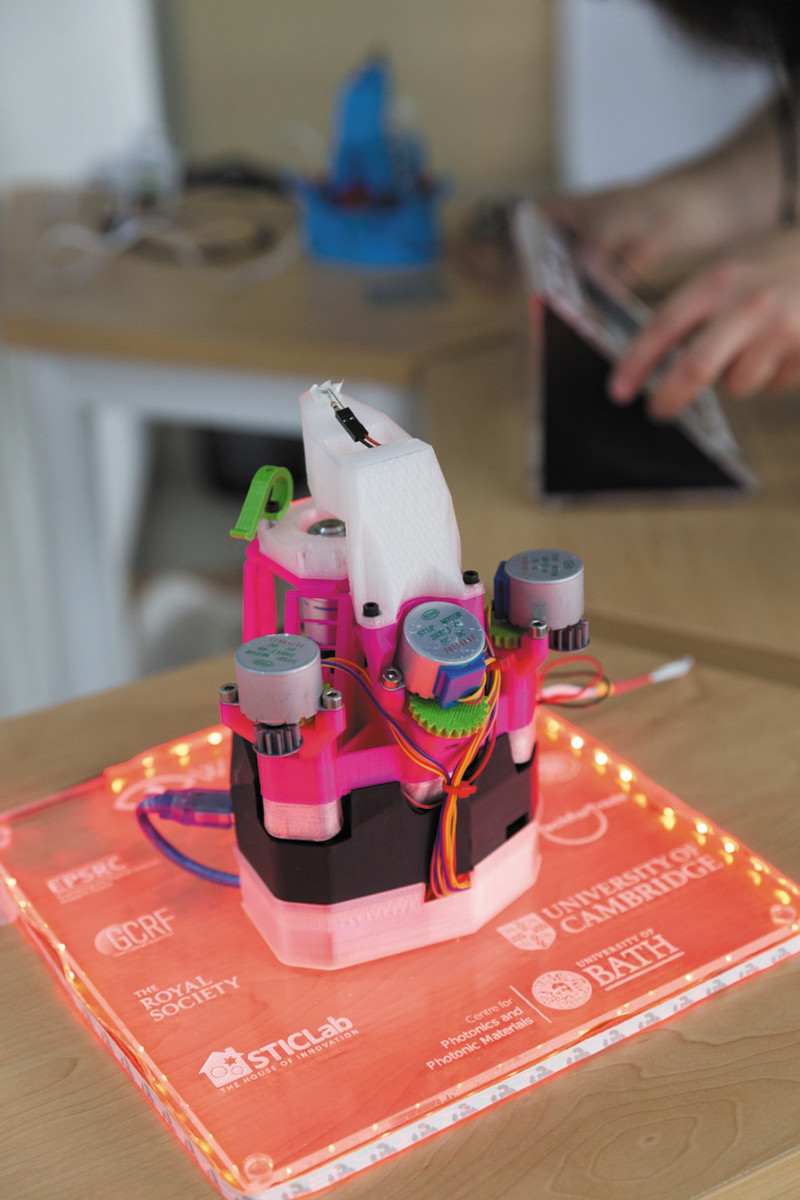

Run Raspberry Pi Imager and pick RetroPie from the choose operating system list. You want the most powerful Raspberry Pi you can lay your hands on, but a Raspberry Pi Zero will do the trick if you stick to emulating relatively early systems, and is great for embedded console projects.

Choose your microSD card, click Write, and give the software permission to overwrite any data on the microSD card. Wait for the image to be downloaded and flashed.

Plug it in, baby

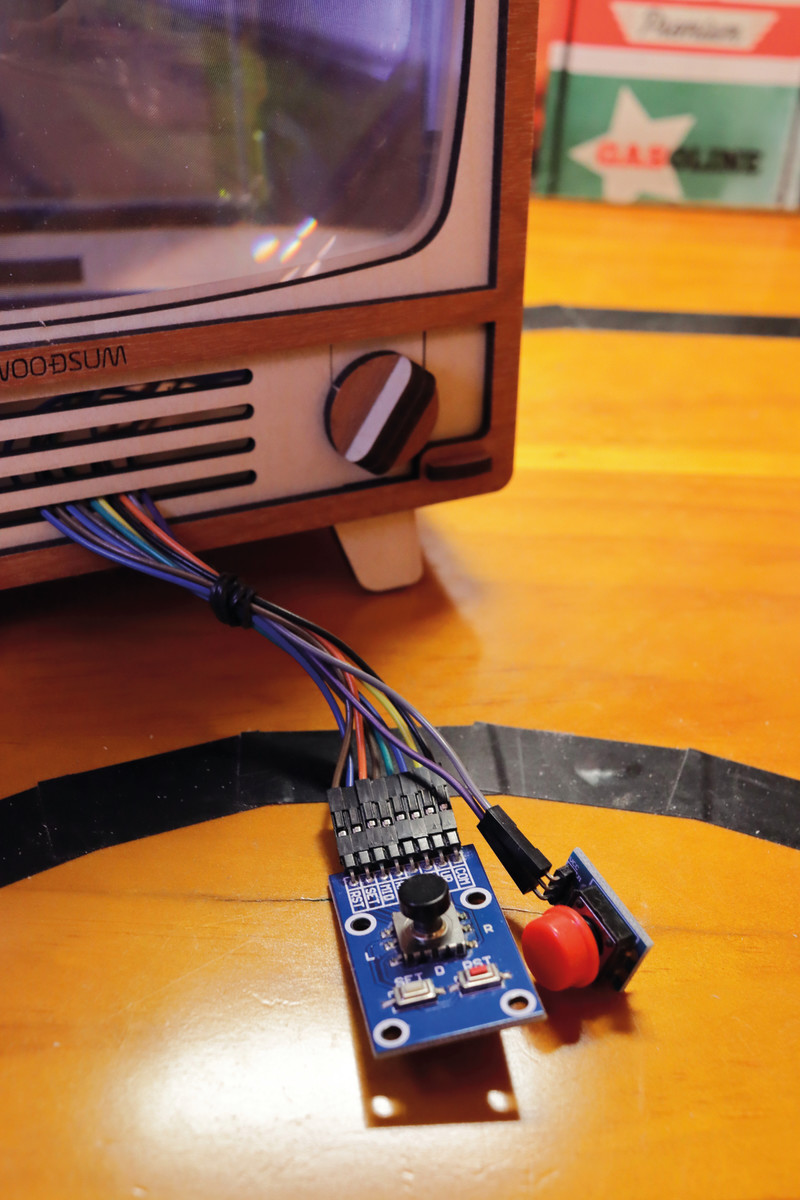

Insert the microSD card and connect Raspberry Pi to a keyboard, mouse, and monitor. If you’ve got controllers or joysticks, plug them in before you power up.

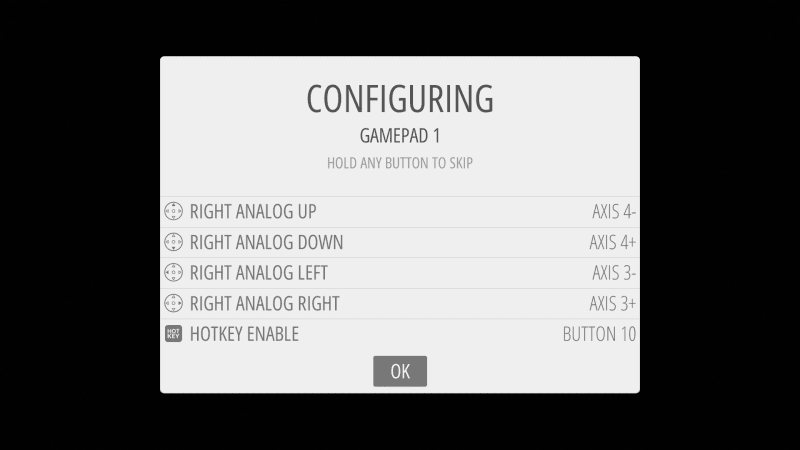

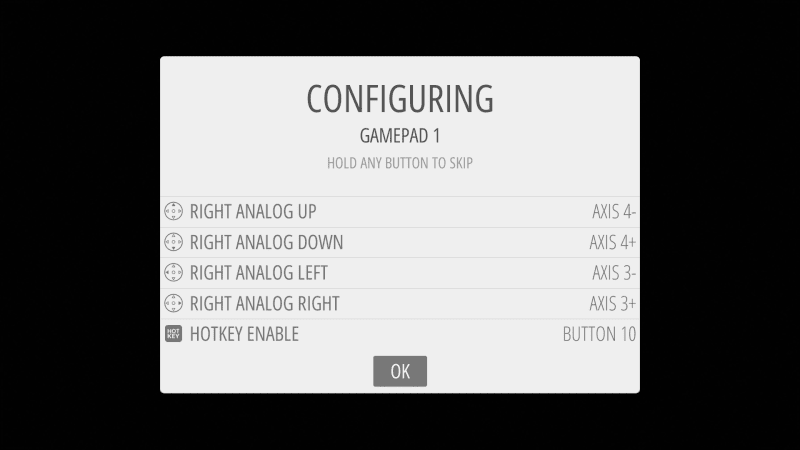

After the image boots, you’ll be prompted to assign your gamepad’s buttons, if you have one. Trigger buttons on some controllers – notably Xbox 360 compatible gamepads – may not register when pressed. Press and hold any other button to skip configuring them for now. If you make a mistake, you’ll be able to go back and correct it when you get to the end of the configuration list.

Fix your triggers (optional)

If the triggers are unresponsive on your Xbox 360 compatible controller, you should update the xpad driver. Go to RetroPie configuration and select RetroPie Setup. From the ncurses menu, select Manage Packages > Manage Driver Packages > 847 Xpad Driver, then Update.

Exit back to the main EmulationStation interface and open the Menu. You may find that this has been remapped from Start to the Right Trigger button after the update. Scroll down and select Configure Input.

Set me up

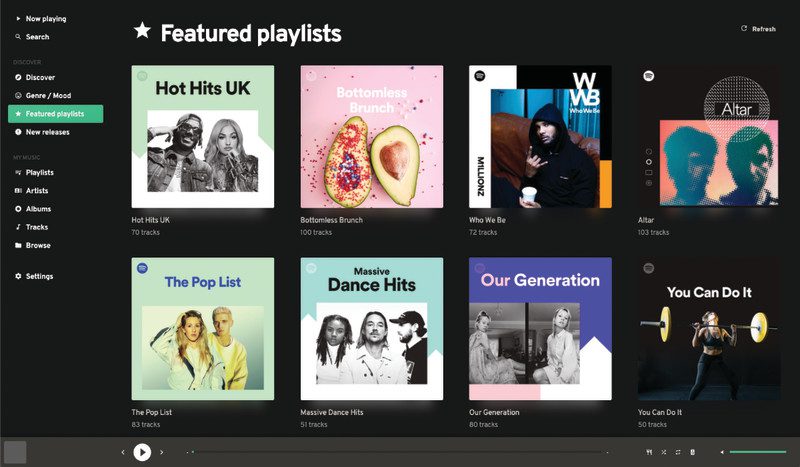

With your controller configured, you’ll be taken to the main interface. You won’t see any emulators on offer until you’ve copied over games for them to play. Press A on RetroPie to enter the config menu.

Select WiFi. Press OK at the following menu to go on to connect to a wireless network. Choose from the network list and enter the network key. Select Exit to return to the main EmulationStation config menu.

Some 1920×1080 displays will show a black border. If this is the case, select raspi-config. Go to Advanced Options, then Overscan – this will get rid of the black border. Select No to disable overscan compensation. You’ll need to reboot for this to take effect.

Get some ROMs

Before we go any further, you’ll need some games to run on RetroPie’s suite of emulators. For our first NES ROM, we’ll grab the Oliver Twins’ Mystery World Dizzy. Go to yolkfolk.com/mwd and click Download. To test Mega Drive emulation, go to arkagis.com and click ‘Download trial version’ to take Arkagis Revolution’s great rotating field navigation for a spin.

It’s easiest to download ROMs on another computer and copy them across your local network to RetroPie’s Samba share at retropie.local using your file manager. Each console has its own subdirectory under the roms directory. Windows users should ensure that network discovery is enabled.

Time to play

Back on Raspberry Pi, restart EmulationStation: press Start on your controller, select Quit, then Restart System. Restart the interface every time you add games to force it to re-check its ROM directories.

If you have a keyboard connected, it’s quicker to press and hold F4 to quit to the command line, then type exit to restart EmulationStation.

As you scroll to the left or right, you should see logos for the NES and Mega Drive. Press A to enter the menu, then press A while highlighting the game you want to play. Right and left directional controls switch between different consoles.

Shortcuts, mods, and fixes

Remember the Hotkey you defined during controller configuration? You’ll be using that a great deal, as it serves as a mode switch for controller shortcuts. You’ll find more info in the docs, but these are the most useful:

-

Hotkey + Start – quit the game

-

Hotkey + Right Shoulder – Save

-

Hotkey + Left Shoulder – Load

-

Hotkey + B – Reset

-

Hotkey + X – Open quick menu for save states, screenshots, recording and similar

If you don’t get any audio from Raspberry Pi 4, make sure the HDMI lead connecting your monitor is plugged into the HDMI 0 port, nearest to the power connector.