Between September 2021 and March 2022, we’ve been partnering with The Alan Turing Institute to host a series of free research seminars about how to young people about AI and data science.

In the final seminar of the series, we were excited to hear from Stefania Druga from the University of Washington, who presented on the topic of AI literacy for families. Stefania’s talk highlighted the importance of families in supporting children to develop AI literacy. Her talk was a perfect conclusion to the series and very well-received by our audience.

Stefania is a third-year PhD student who has been working on AI literacy in families, and since 2017 she has conducted a series of studies that she presented in her seminar talk. She presented some new work to us that was to be formally shared at the HCI conference in April, and we were very pleased to have a sneak preview of these results. It was a fascinating talk about the ways in which the interactions between parents and children using AI-based devices in the home, and the discussions they have while learning together, can facilitate an appreciation of the affordances of AI systems. You’ll find my summary as well as the seminar recording below.

“AI literacy practices and skills led some families to consider making meaningful use of AI devices they already have in their homes and redesign their interactions with them. These findings suggest that family has the potential to act as a third space for AI learning.”

– Stefania Druga

AI literacy: Growing up with AI systems, growing used to them

Back in 2017, interest in Alexa and other so-called ‘smart’, AI-based devices was just developing in the public, and such devices would have been very novel to most people. That year, Stefania and colleagues conducted a first pilot study of children’s and their parents’ interactions with ‘smart’ devices, including robots, talking dolls, and the sort of voice assistants we are used to now.

Working directly with families, the researchers explored the level of understanding that children had about ‘smart’ devices, and were surprised by the level of insight very young children had into the potential of this type of technology.

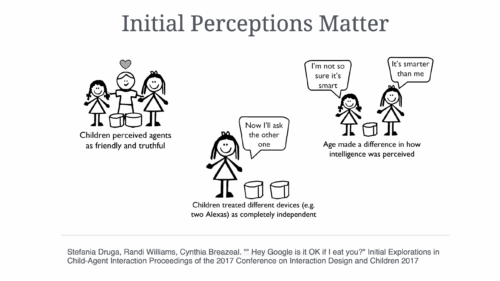

In this AI literacy pilot study, Stefania and her colleagues found that:

- Children perceived AI-based agents (i.e. ‘smart’ devices) as friendly and truthful

- They treated different devices (e.g. two different Alexas) as completely independent

- How ‘smart’ they found the device was dependent on age, with older children more likely to describe devices as ‘smart’

AI literacy: Influence of parents’ perceptions, influence of talking dolls

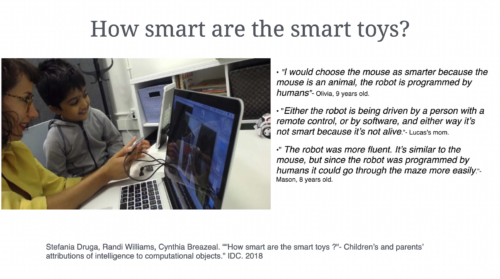

Stefania’s next study, undertaken in 2018, showed that parents’ perceptions of the implications and potential of ‘smart’ devices shaped what their children thought. Even when parents and children were interviewed separately, if the parent thought that, for example, robots were smarter than humans, then the child did too.

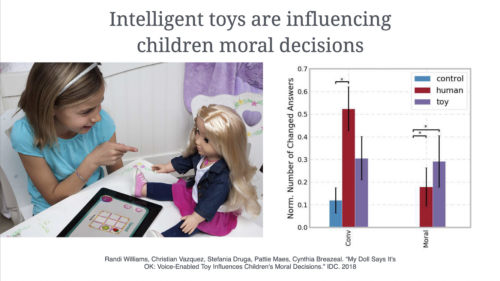

Another part of this study showed that talking dolls could influence children’s moral decisions (e.g. “Should I give a child a pillow?”). In some cases, these ‘smart’ toys would influence the child more than another human. Some ‘smart’ dolls have been banned in some European countries because of security concerns. In the light of these concerns, Stefania pointed out how important it is to help children develop a critical understanding of the potential of AI-based technology, and what its fallibility and the limits of its guidance are.

AI literacy: Programming ‘smart’ devices, algorithmic bias

Another study Stefania discussed involved children who programmed ‘smart’ devices. She used the children’s drawings to find out about their mental models of how the technology worked.

She found that when children had the opportunity to train machine learning models or ‘smart’ devices, they became more sceptical about the appropriate use of these technologies and asked better questions about when and for what they should be used. Another finding was that children and adults had different ideas about algorithmic bias, particularly relating to the meaning of fairness.

AI literacy: Kinaesthetic activities, sharing discussions

The final study Stefania talked about was conducted with families online during the pandemic, when children were learning at home. 15 families, with in total 18 children (ages 5 to 11) and 16 parents, participated in five weekly sessions. A number of learning activities to demonstrate features of AI made up each of the sessions. These are all available at aiplayground.me.

The fact that children and parents, or other family members, worked through the activities together seemed to generate fruitful discussions about the usefulness of AI-based technology. Many families were concerned about privacy and what was happening to their personal data when they were using ‘smart’ devices, and also expressed frustration with voice assistants that couldn’t always understand the way they spoke.

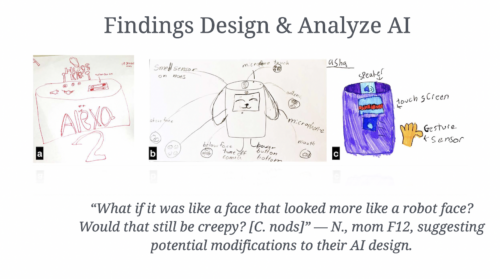

In one of the sessions, with a focus on machine learning, families were introduced to a kinaesthetic activity involving moving around their home to train a model. Through this activity, parents and children had more insight into the constraints facing machine learning. They used props in the home to experiment and find out ways of training the model better. In another session, families were encouraged to design their own devices on paper, and Stefania showed some examples of designs children had drawn.

This study identified a number of different roles that parents or other adults played in supporting children’s learning about AI, and found that embodied and tangible activities worked well for encouraging joint work between children and their families.

Find out more

You can catch up with Stefania’s seminar below in the video, and download her presentation slides.

More about Stefania’s work can be learned in her paper on children’s training of ML models and also in her latest paper about the five weekly AI literacy sessions with families.

Recordings and slides of all our previous seminars on AI education are available online for you, and you can see the list of AI education resources we’ve put together based on recommendations from seminar speakers and participants.

Join our next free research seminar

We are delighted to start a new seminar series on cross-disciplinary computing, with seminars in May, June, July, and September to look forward to. It’s not long now before we begin: Mark Guzdial will speak to us about task-specific programming languages (TSP) in history and mathematics classes on 3 May, 17.00 to 18.30pm local UK time. I can’t wait!

Sign up to receive the Zoom details for the seminar with Mark:

Website: LINK

Schreibe einen Kommentar

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.