Schlagwort: raspberrypi

-

PiFi review: mobile wireless access solution

Reading Time: 2 minutesEnter, PiFi, a simple kit that allows you to easily create a fast and secure wireless network with just a Raspberry Pi. The kit comes with just three items: a microSD card with the software preloaded, an Ethernet cable to plug into the nearest router, and the all-important Wi-Fi dongle that handles…

-

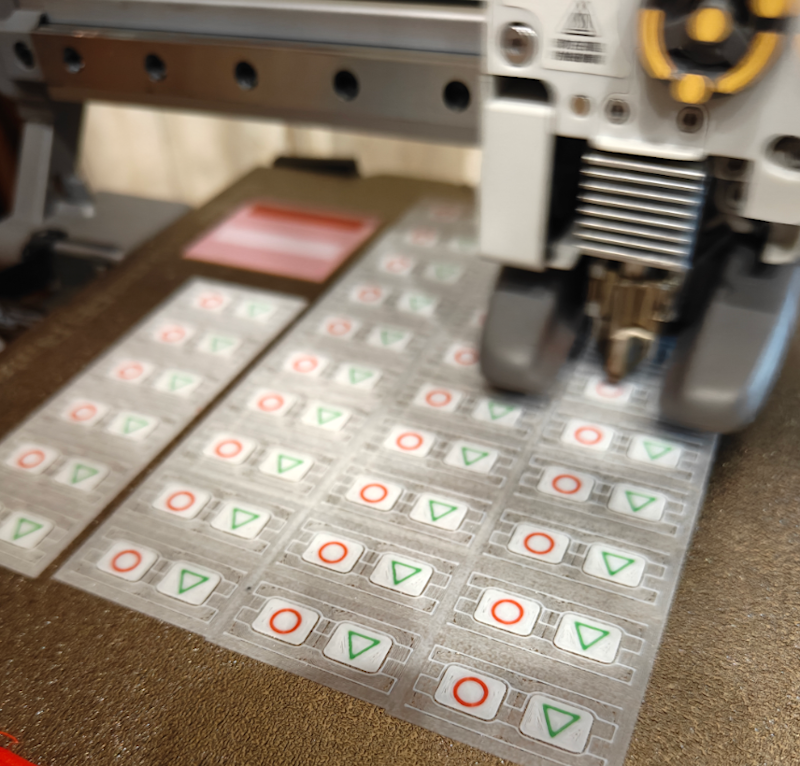

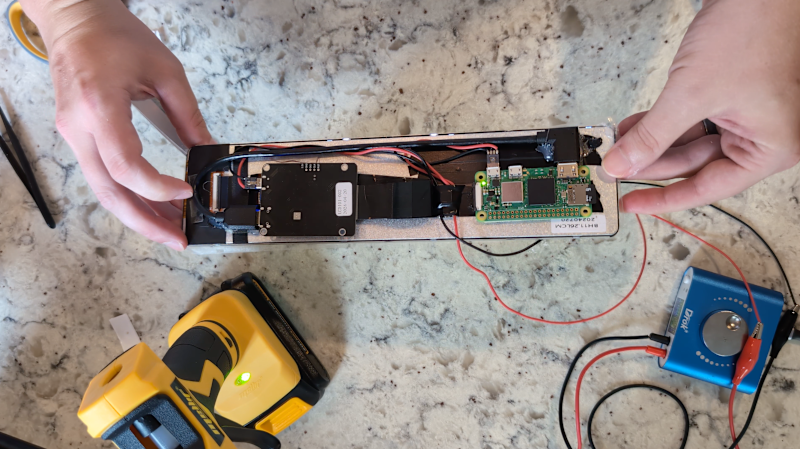

Hackberry Pi Zero

Reading Time: 4 minutes“I was inspired to create the Hackberry Pi Zero about three years ago when I found a project about reverse-engineering on Hackaday,” Zitao says. “I thought it would be really cool to have a device with a thumb keyboard, so I began reverse-engineering old BlackBerry keyboards and made it technically work. I…

-

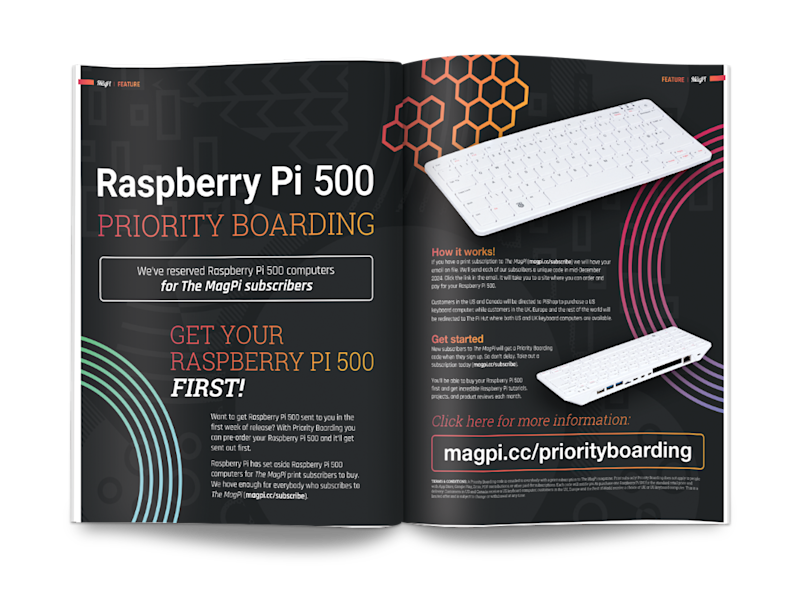

Raspberry Pi 500 and Monitor in The MagPi 149

Reading Time: 3 minutesThe latest edition of The MagPi covers all the new products in depth, with detailed specifications, documentation, and interviews with the CM5 engineer. We’ve also got information on the new Raspberry Pi Pico 2 W, Raspberry Pi Hub, and Raspberry Pi Connect service. There’s a lot of new products this month and…

-

Win! One of five Raspberry Pi Monitors

Reading Time: < 1 minuteWe’ve been looking forward to the new Raspberry Pi Monitor for ages now – the inexpensive and lightweight display is perfect for so many uses, whether you’re in a classroom, at your desk, or on the go. We have five to giveaway, and you can enter the competition below…

-

Wax: digital music manager

Reading Time: 4 minutesWax differs from most existing music managers in three ways. Instead of individual tracks, music is catalogued as ‘works’ – such as an album, a symphony, an opera, etc. Secondly, works are categorised by genre, but it also allows you to tag works in a way that is relevant to the genre…

-

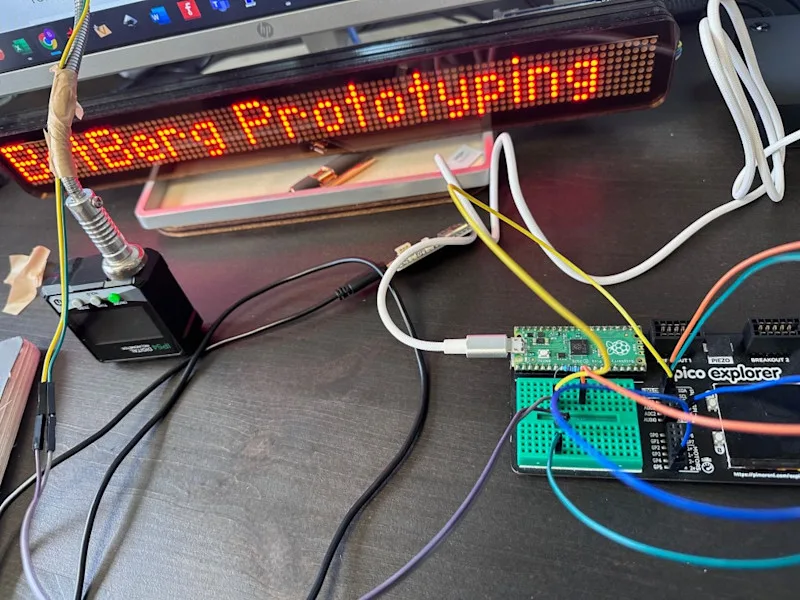

Bumpin‘ Sticker

Reading Time: 5 minutes“I love the idea of using bumper stickers as a form of self-expression, but I got to thinking about how ‘permanent’ they are, and how my own style, mood and taste tends to change relatively quickly,” he says. “I wanted to see how I could resolve those things – could I make…

-

T-Rex Game Auto Jumper

Reading Time: 2 minutes“Using a Raspberry Pi Pico, a light dependent resistor (LDR), a breadboard, some DuPont cables, and tape, I automated the famous Google T-Rex game,” Bas explains. “The LDR detects differences in analogue measurements whenever it senses cacti, which are always dark-coloured and appear on the same plane. The analogue-digital converter [ADC] port…

-

Argon Poly+ 5 Raspberry Pi case review

Reading Time: 2 minutesThe Poly+ 5 is a Raspberry Pi 5 case in two flavours and colours. The case itself is moulded plastic with none of the aluminium work we’ve come to expect. The slightly transparent slidable top cover is available in red or black with a black base in both cases. The standard model…

-

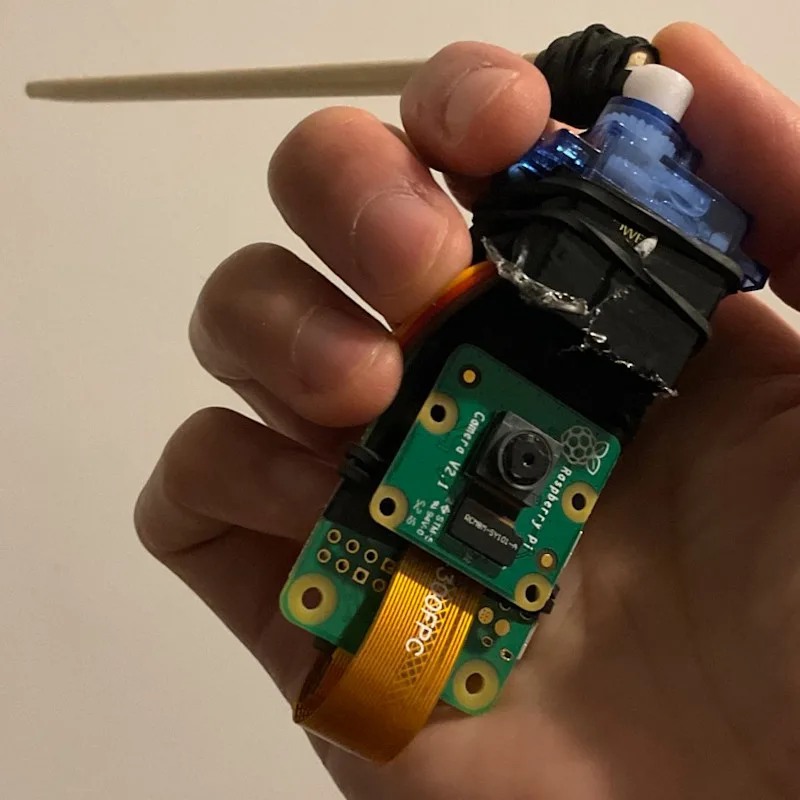

CatBot animal feeder

Reading Time: 2 minutes“I used Raspberry Pi because I was recently working with Raspberry Pi and cameras for another project, a digital sensor for a film camera,” says Michael. “Although there are definitely simpler solutions with cheaper microcontrollers, I find it valuable to start with techniques I know rather than going down rabbit holes of…

-

Putting AI to use

Reading Time: < 1 minuteLucy Hattersley has all the AI kit and an urge to build something real

-

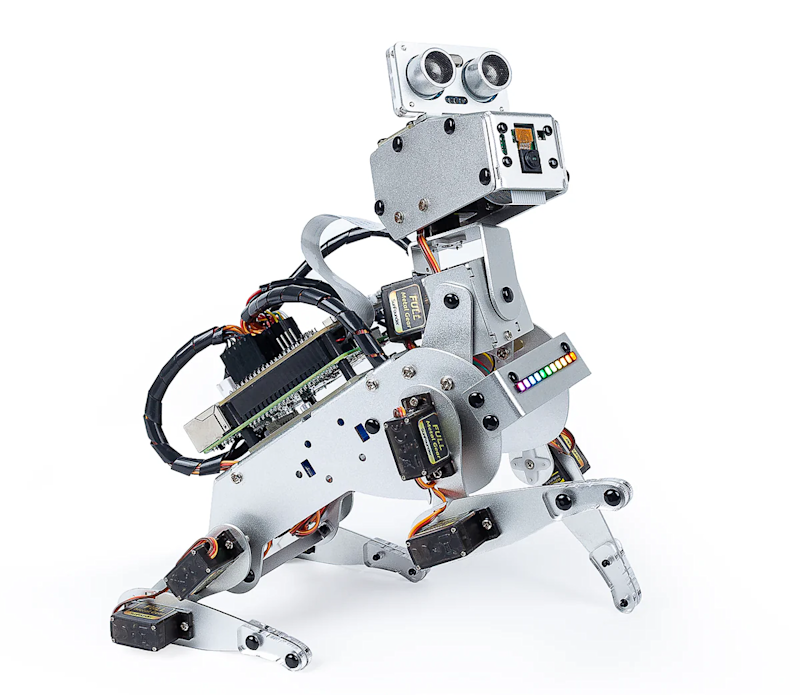

PiDog robot review

Reading Time: 3 minutesThe first thing to decide is which Raspberry Pi model to use before assembling the kit. PiDog will work with Raspberry Pi 4, 3B+, 3B, and Zero 2 W. Using a Raspberry Pi 5 is not recommended since its extra power requirements put too much of a strain on the battery power…

-

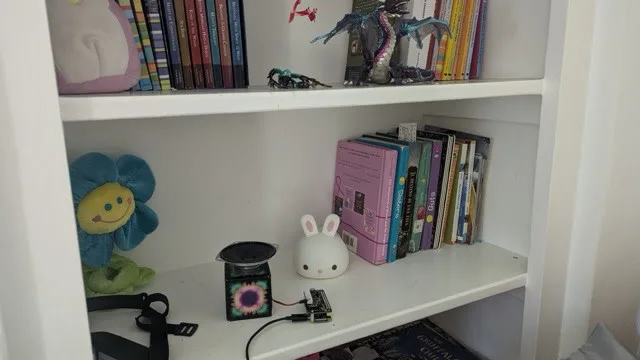

Fably bedtime storyteller

Reading Time: 3 minutesChildhood wonder Stefano’s first computer, a Commodore Vic20, was something he could program himself and opened up a world of possibilities. Most importantly, this first computer awakened Stefano to the idea of tinkering and eventually led to him pursuing a degree in electronic engineering. Over the past 20 years he has worked…

-

Gear Guide 2025 in The MagPi magazine issue 148

Reading Time: 2 minutesGear Guide 2025! Our Gear Guide 2025! has your back. Discover a treasure trove of Raspberry Pi devices and great accessories taking us into a glittering new year. Gift a project Sometimes the perfect gift is one you made yourself. Christmas Elf, Rob Zwetsloot has a fantastic feature for constructing your gifts…

-

Win one of three Thumby Color game systems

Reading Time: < 1 minuteA ton of supporting products launcged with Raspberry Pi Pico 2 and the RP2350, including a lot of items that were powered by RP2350. One of these included the excellent Thumby Color game system, and we finally have a few for a competition – enter below…

-

Pibo the bipedal robot review

Reading Time: 2 minutesIt comes fully assembled, which is very nice as putting together the various motors and other components together correctly has been a pain with similar products in the past. All you need to do is turn it on and get it connected to your Wi-Fi network, either via a wireless access point…

-

AI special edition in The MagPi 147

Reading Time: 2 minutesAI Projects Discover a range of practical AI Projects that put Raspberry Pi’s AI smarts to good use. We’ve got people detectors, ANPR trackers, pose detectors, text generators, music generators, and an intelligent pill dispenser. Handheld gaming Retro gaming on the move can be fun and creative. PJ Evans grabs some spare…

-

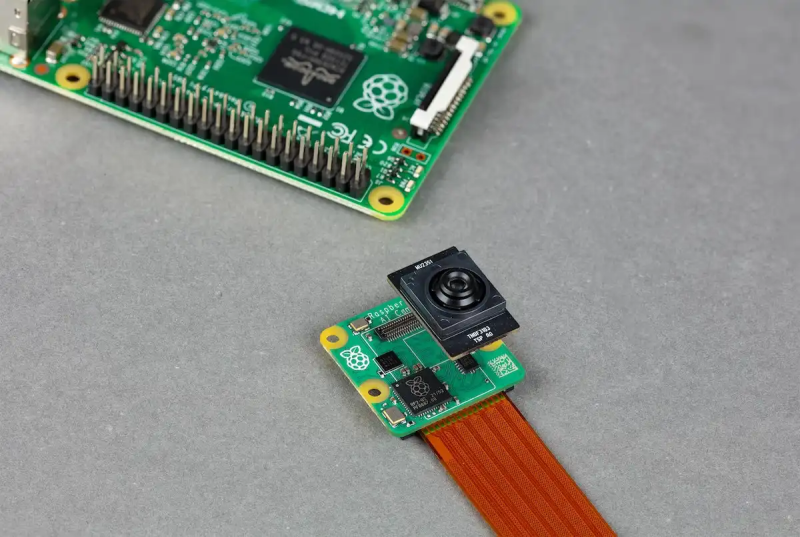

Win! One of five brand new Raspberry Pi AI Cameras

Reading Time: < 1 minuteSave 35% off the cover price with a subscription to The MagPi magazine. UK subscribers get three issues for just £10 and a FREE Raspberry Pi Pico W, then pay £30 every six issues. You’ll save money and get a regular supply of in-depth reviews, features, guides and other Raspberry Pi…

-

Open Source Hardware Camp

Reading Time: 3 minutesFriday kicked off with a talk on Dina St Johnston, founder of the UK’s first independent software company, which she started in 1959. After that came computing with human-worn sensors; mainframes; human creativity in the age of AI; and a look at Raftabar the robot, which uses facial recognition (and two Raspberry…

-

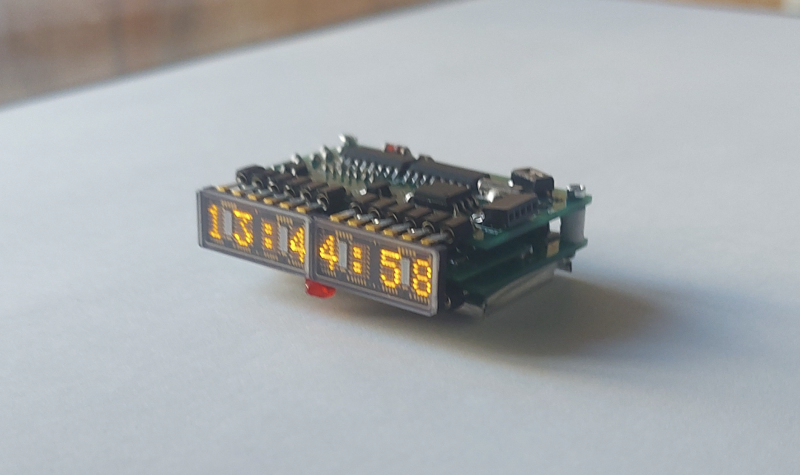

HDSP wristwatch

Reading Time: < 1 minuteWith a six-digit, seven-segment display such as the HDSP-2000 (itself an unusual choice – he hasn’t made this easy), Vitalii needed to find a way to multiplex the signals coming out of the chip, multiplying the I/O signals with transistors until he had enough to control each of the segments in…

-

Arcade briefcase

Reading Time: < 1 minuteAlternatively, if you have access to a soldering iron and a drill, you can build your own home arcade setup. This build by SrGamer is based on a Raspberry Pi 5, and features two joysticks, loads of buttons and a gloriously chunky red power switch built into the case. The case…

-

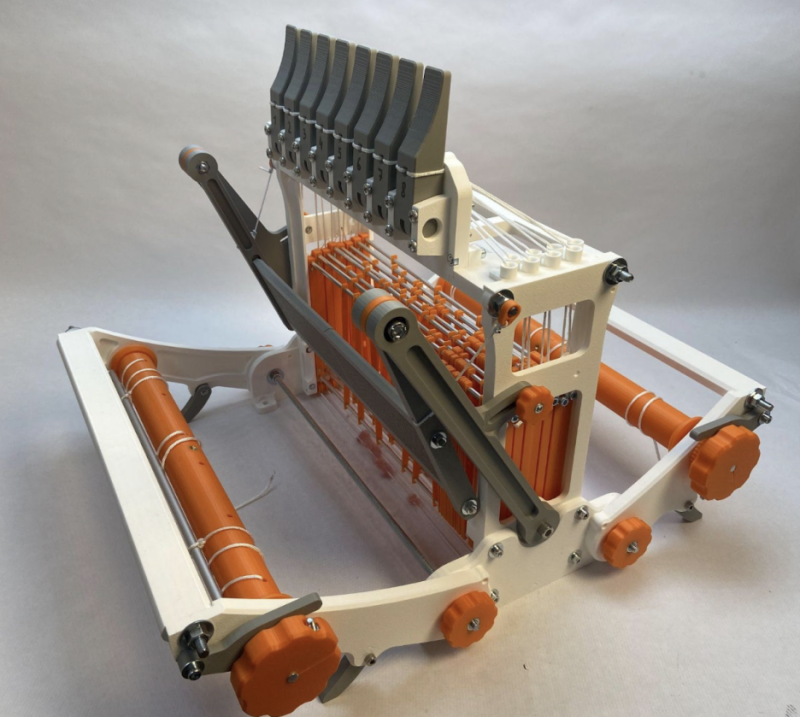

3D-printed loom

Reading Time: < 1 minuteIf you’ve ever tried to specialise in any field of making, you’ll find that at some point you’ll have stopped – or at least delayed – creating things, in order to make things that help you make things. If you’re at the start of your journey into woodworking, for example, you’ll…

-

Meet Natalie Turner: one of our magazine designers

Reading Time: 2 minutesHow did you join Raspberry Pi? I was working part time alongside job hunting after uni, and came across the application for a graphic design role at Raspberry Pi. I then got invited for an interview where I got to meet my lovely team, and speak through a few of my projects.…