Schlagwort: install instructions

-

Adapting our computing curriculum resources for Kenya — the journey so far

Reading Time: 4 minutesYoung people everywhere deserve a high-quality computing education. But what a high-quality computing education looks like differs depending on a learner’s culture, context, and the existing provision in the country they live in. Therefore, adapting our educational resources for a range of contexts is a key part of our work at the…

-

Young creators on the move at Coolest Projects Belgium 2025

Reading Time: 3 minutesThis year marked the 10th anniversary of Coolest Projects Belgium. The meticulously organised event was held in April by our partner CoderDojo Belgium, at Technopolis in Mechelen. Themed ‘On the move’, the event invited young creators to interpret movement however they liked – which they did in an impressive number of ways,…

-

From player to maker: Learn to code by creating your own game

Reading Time: 3 minutesAt Code Club, we believe learning to code should be as fun as it is empowering — what better way to start than making your own game? Whether it’s about pixelated pirates, racing robots, or a time-travelling llama, creating a game is one of the most exciting ways to explore coding. We’ve…

-

How to give your students structure as they learn programming skills

Reading Time: 5 minutesCreating a computer program involves many different skills — knowing how to code is just one part. When we teach programming to young people, we want to guide them to learn these skills in a structured way. The ‘levels of abstraction’ framework is a great tool for doing that. This blog describes…

-

Igniting innovation: How Experience AI is empowering teachers and students across Kenya

Reading Time: 4 minutesThis blog post is written by Victor Murithi, Communications and Media Consultant at Young Scientists Kenya, one of our global partners for Experience AI in Kenya. When over 100 teachers from across Kenya gathered at Kangaru High School in Embu County for the Kenya Science and Engineering Fair Nationals in April, few…

-

Bringing data science to life for K–12 students with the ‘API Can Code’ curriculum

Reading Time: 7 minutesAs data and data-driven technologies become a bigger part of everyday life, it’s more important than ever to make sure that young people are given the chance to learn data science concepts and skills. David Weintrop Rotem Israel-Fishelson Peter F Moon In our April research seminar, David Weintrop, Rotem Israel-Fishelson, and Peter…

-

Astro Pi 2024/25: Another stellar year of space education concludes

Reading Time: 4 minutesWe’re thrilled to celebrate yet another incredible year of young people reaching for the stars, as the European Astro Pi Challenge 2024/25 draws to a close. Teams from across Europe and ESA Member States are now receiving their well-deserved certificates and data from the International Space Station (ISS). It’s been a truly…

-

Discover the incredible impact of Code Club: The Code Club annual survey report 2025

Reading Time: 3 minutesWe’re pleased to share highlights from the 2025 Code Club annual survey report today, showcasing another year of incredible achievements and the positive impact of the global Code Club community. Code Club is a global movement of free coding clubs where school-aged young people — called creators — develop the confidence to…

-

Join our free data science education workshop for teachers

Reading Time: 2 minutesAre you a teacher who is interested in data science education for key stage 5 (age 16 to 18)? Then we invite you to join our free, in-person workshop exploring the topic, taking place in Cambridge, UK on 10 July 2025. You will be among the very first educators to see some…

-

Why kids still need to learn to code in the age of AI

Reading Time: 3 minutesToday we’re publishing a position paper setting out five arguments for why we think that kids still need to learn to code in the age of artificial intelligence. Generated using ChatGPT. Just like every wave of technological innovation that has come before, the advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are raising profound questions…

-

Young tech creators take over Bradford at Coolest Projects UK

Reading Time: 5 minutesBradford was buzzing with excitement this May as over 170 young digital makers from across the UK gathered for Coolest Projects UK 2025 at the Life Centre to celebrate the amazing things young people create with technology. Run by the Raspberry Pi Foundation and hosted by BBC science presenter Greg Foot, the…

-

Bridging the divide: Connecting global communities with Experience AI

Reading Time: 6 minutesFrom smart devices to workplace tools, AI is becoming part of everyday life and a major part of how people are thinking about the future — raising big questions about access, skills, and readiness. As governments around the world create AI strategies for the decade ahead, many are seeing an urgent need…

-

Beyond phone bans: Empowering students to critically navigate and reimagine technology

Reading Time: 6 minutesAmidst heated discussion of smartphones and their impacts on young people’s lives, it’s become a frequent recommendation to ban phones in schools. Below I summarise the research evidence on smartphone bans (it’s mixed) and share tips for computing educators on how to constructively address the topic with their learners and empower them…

-

Teaching digital literacy without devices

Reading Time: 5 minutesLack of access to devices presents teachers with challenges in any setting. In schools, money is often limited and digital technology may not be the priority when buildings need maintenance or libraries need replenishing. This issue is particularly important when the very subject you teach relies on and relates to devices that…

-

Experience CS: A safe, creative way to teach computing

Reading Time: 3 minutesExperience CS is our new free curriculum that helps elementary and middle school educators (working with students aged 8 to 14) teach computer science with confidence through creative, cross-curricular lessons and projects. Designed for teachers, by teachers, Experience CS is built to be easy to use in classrooms, with everything you need…

-

Research insights to help learners develop data awareness

Reading Time: 7 minutesAn increasing number of frameworks describe the possible contents of a K–12 artificial intelligence (AI) curriculum and suggest possible learning activities (for example, see the UNESCO competency framework for students, 2024). In our March seminar, Lukas Höper and Carsten Schulte from the Department of Computing Education at Paderborn University in Germany shared…

-

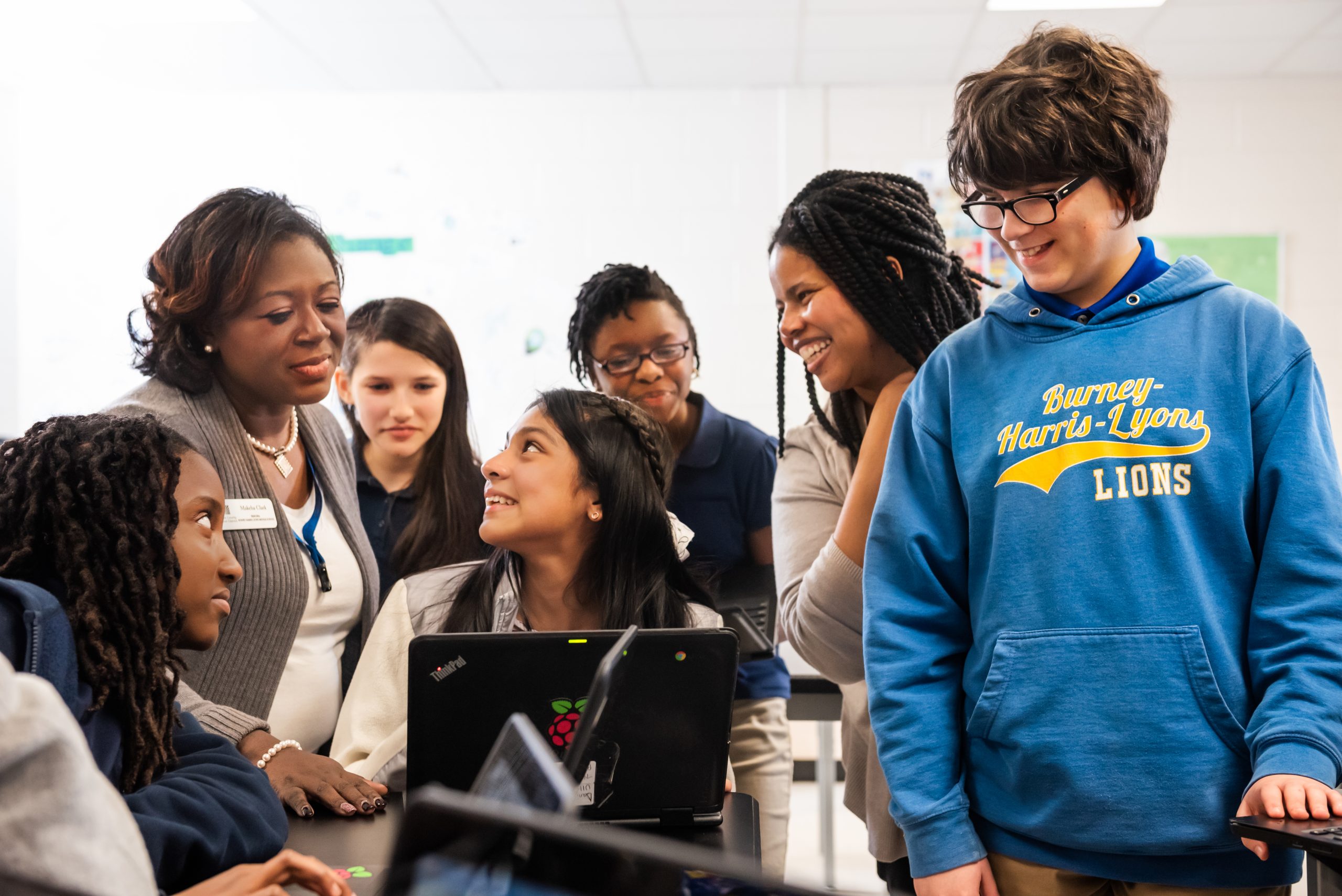

How to bring digital literacy into your classroom: practical tips from the Hello World podcast

Reading Time: 4 minutesAre you looking to strengthen digital literacy in your classroom? In the latest episode of the Hello World podcast, three experienced teachers from the USA and the UK share practical tips they’ve used in their classrooms to help their students build digital literacy. Whether you’re just getting started with digital literacy or…

-

Raspberry Pi Foundation joins UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition

Reading Time: 3 minutesIntroduction We are thrilled to announce that the Raspberry Pi Foundation (RPF) has been accepted as a member of UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition (GEC). Initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when 1.6 billion learners were shut out of the classroom, the GEC aimed to provide continuity of education in times of crisis. Since…

-

Hello World #26 out now: Digital Literacy

Reading Time: 4 minutesWe often believe we understand the meaning of ‘digital literacy’, but it can be a misleading term. Do we mean digital skills? Online safety? Where does AI fit in? As computer science education evolves to meet the needs of our increasingly digital world, we believe that true digital literacy empowers young people…

-

Supporting teachers to integrate AI in K–12 CS education

Reading Time: 5 minutesTeaching about artificial intelligence (AI) is a growing challenge for educators around the world. In our current seminar series, we are gaining insights from international computing education researchers on how to teach about AI and data science in the classroom. In our second seminar, Franz Jetzinger from the Technical University of Munich,…

-

Empowering India’s digital future: Our computing curriculum’s impact

Reading Time: 3 minutesThe Raspberry Pi Foundation has been working in India since 2018 to enable young people to realise their potential through the power of computing and digital technologies. We’ve supported Code Clubs, partnered with government organisations, and designed and delivered a complete computing curriculum for students in grades 6 to 12 and at…

-

Experience CS: a new way to teach computer science

Reading Time: 4 minutesI am delighted to announce Experience CS, a free, integrated computer science curriculum for elementary and middle school students (8–14 years old) that will be available in June 2025. Experience CS enables educators to teach computer science through a standards-aligned curriculum that integrates computer science concepts and knowledge into core subjects like…