As adults, it’s easy for us to see the impact technology has had on society and on our lives. Yet when I tell pupils that, within my lifetime, it wasn’t always illegal to hold your mobile phone to your ear and have a call while driving, they are horrified. They are living in the now and don’t yet have the perspective to allow them to see the change that has happened.

With the greater understanding we now have of technology and its impact, we can better learn from previous mistakes, make decisions around ethical behaviour (such as whether to use a phone while driving), and critically engage in real-world issues.

As teachers, allocating some time to this topic throughout the year can seem challenging, but by implementing a few small changes, the benefits might be more than you imagine. Here are three ways you can help your students explore the impact of technology.

1. Change the format of your lessons by stepping away from devices

As teachers know, some computing lessons work best when students don’t use devices, whether it’s a matter of students designing programs before starting to code them, drawing maps of their school network, or discussing the implications of bias in AI training models. It’s important that learners recognise that computers are tools — sometimes they allow us to do and achieve great things, but sometimes there are other approaches that are more suitable.

Spending time discussing the impact of technology can help learners decide for themselves when technology is an asset, and when it is a burden. Another advantage of changing the format of your computing lessons away from device usage is that they may appeal to a wider range of students. While some students may not be interested in using technology, they may enjoy debating ethics, discussing world events, or finding solutions to real-world problems — all of which can take centre stage in a more discussion-focused computing lesson.

This approach can also demonstrate to your class that lots of different skill sets are needed in the computing industry, and inspire your learners to consider career paths they might have otherwise dismissed. In addition, open, discussion-based lessons can give your learners food for thought, encouraging them to approach tasks in subsequent lessons with a greater appreciation of broader issues — whether they’re designing a program, deciding what features to build into a website, or how to structure a database.

2. Connect your lessons to real-world events

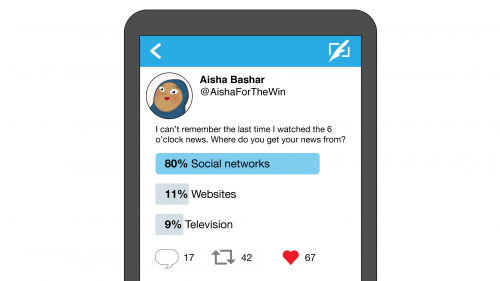

Young people exist in an interesting space when it comes to world events. Even if they’re not engaged in current affairs, they’ll probably still encounter a lot of content about what’s happening in the world. They may see snippets of news footage on television, hear adults talking about a big event, or — with so much of their lives now happening online — stumble across trending stories and associated opinions while using social media, apps, and websites.

Young people will often try to make sense of all these bits of information, filling in the blanks. The problem is that if we don’t talk to young people about what they’re hearing, they may fill in the blanks incorrectly. Before you know it, they might be anxious that artificial intelligence will take over the world, or that adults hate TikTok for no reason.

It’s important to equip young people with the skills to think about real-world events — and developments related to technology — critically and calmly.

Headlines such as “Why the USA is banning TikTok” or self-help articles with titles like “Why muting people on social media will change your life” could make brilliant focus points for a lesson or activity about the impact of technology. Discussing these kinds of headlines and articles can help your learners consider their own opinions, apply what they know about how technology works, and gain a sense of grounding in our often turbulent world.

By encouraging your learners to articulate what they know and apply it to real-world situations, you’ll enrich their computing education while also nurturing responsible digital citizens.

3. Encourage students to have difficult conversations

The role of a computing teacher is often broad. Beyond curriculum and teaching responsibilities, it will usually involve providing tech support (changing ink in printers, for instance) and dealing with safeguarding incidents that have happened between pupils at the weekend.

Safeguarding is a key part of teaching. Effective safeguarding should include teaching your learners about what to do in difficult scenarios, like when a WhatsApp group goes awry, when an image is shared on social media when it shouldn’t have been, or when a game becomes popular that your learners aren’t old enough to play.

Each of these scenarios is an example of technology’s impact on our lives. It’s important that your learners know how to deal with these scenarios and can have different opinions while talking and listening to each other. Also, if your learners can do these things, it will make things easier in the future if you need to talk to a particular learner about something inappropriate they’ve done.

By encouraging your learners to have difficult conversations, you’ll practise how to navigate the tension between legality, rules from home, and best-practice advice from external sources. You’ll also have lessons that you can refer back to: “Remember when we were discussing the TikTok ban? How might some of those conversations relate to this situation? What about when we discussed when to block people on games or on social media? Would that be appropriate here?”

Raising awareness that the impact of technology can enrich lessons

Technology is going to continue to impact the lives of the pupils we work with, whether they can recognise that or not. Increasing their awareness of the impact technology is having, in both positive and negative ways, will enrich your lessons, show that content is relevant to your learners, and help protect them when they have to make their own critical decisions.

There are suggestions in this article to use with learners of all ages, but if you want more support on how to teach the topic with older learners, we have an online course for educators (helloworld.cc/impactoftech) and a unit of work for 14-year-olds (helloworld.cc/ks4impact).

A version of this article also appears in Hello World issue 24.

Website: LINK