In our latest podcast miniseries, we spoke to educators live from the CSTA 2025 annual conference in Cleveland, Ohio, to hear their top tips for integrating computer science (CS) into other subjects.

Hello World editor, Meg Wang and the team met teachers in the exhibit hall for real-time reflections and essential teacher tips on teaching cross-curricular CS. They spoke to some amazing educators from across the United States and had a great time interacting with everyone in attendance.

“Meeting teachers and hearing first-hand about their experiences, challenges, and triumphs was invaluable. It was amazing to meet Hello World writers in person, and to also meet future writers. Like I said at the conference, Hello World is for educators, by educators, so that means you! Everyone has valuable experience or useful advice to share, and we’re here to help you amplify that.” – Meg Wang, editor of the Hello World magazine

Who features in the episode, and what are their tips?

Lisa Wenzel, CS teacher from Maryland, USA

Lisa’s top tip for integrating computer science into your lessons is to start with topics that you’re passionate about. If you’re not a CS teacher yourself, Lisa suggests finding a colleague who teaches the subject. She advises having a chat with them to explore how you can include CS concepts into subjects you’re particularly interested in.

“I guarantee you that they’re going to have something […] to teach [another subject], and it’s going to involve computer science.”

Through peer discussions and collaboration between educators, you’ll discover engaging ways that you can incorporate CS into your teaching. Give it a try the next time you’re chatting to a CS teacher.

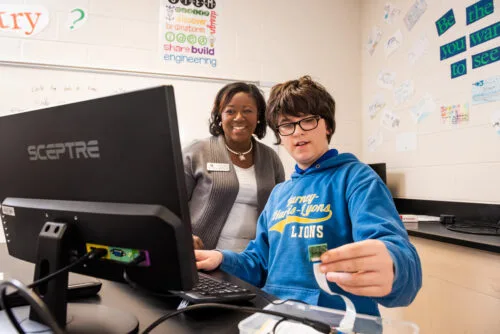

Tiffany N. Jones, CS and Cybersecurity teacher in Georgia, USA

Tiffany N. Jones, author of ‘Belonging in Tech’ (featured on page 82 of Hello World Issue 27), shares her top tip to seamlessly integrate computer science into other subjects.

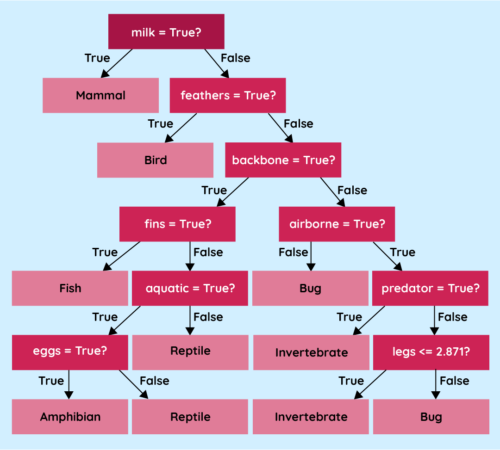

Using the example of a class studying ocean health and pollution, Tiffany shares how you can introduce students to real-world applications of computer science by exploring how sensors and microcontrollers can be used to collect environmental data.

She then suggests exploring how databases and programming languages can be used to analyse and visualise the data that the sensors and microcontrollers have recorded. This not only deepens your learner’s scientific understanding but also demonstrates how computing concepts are used in real-world industry practices.

Rick Ballew, CS and Engineering teacher in Minnesota, USA

Rick’s top tip for integrating CS is to first think about your favourite lesson and consider ways that you can introduce computational thinking.

In the podcast, Rick says:

“chances are, computational thinking is already a part of that lesson you’re doing. Call it out to the students, and that’s going to help them to start understanding how computer science is baked into everything we do.”

Rick also offers a great example from his experience as a band teacher. He shares how learning to read a new piece of music is very similar to the steps involved in computational thinking. s

“[You’ve] got to break it down. There’s abstraction. You’ve got to figure out the sequencing, and you create the way that you’re going to learn it. And that is all part of computational thinking.”

This approach shows students that CS isn’t just coding; it’s a way of thinking that can be applied across disciplines.

Listen now

To hear more practical teacher tips and discover what else our guest teachers had to say, listen to or watch the full episode here.

We hope this episode inspires you and helps you to engage your students in computing. We’d love to hear your thoughts, your feedback, and any of your own tips on how to integrate CS into other subjects. Share your advice in the comments section below.

We hope you enjoy the episode!

More to listen to next week

Next week, we’ll be sharing an interesting conversation between Ben Garside, Senior Learning Manager (AI Literacy) at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, Leonida Soi, Learning Manager (Kenya) at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, and two of our global Experience AI partners, Monika Katkutė-Gelžinė from Vedliai in Lithuania, and Aimy Lee from Penang Science Cluster in Malaysia.

They’ll be exploring what AI education looks like around the world and what teachers need to feel confident teaching it.

You can watch or listen to each episode of our podcast on YouTube, or listen via your preferred audio streaming service, whether that’s Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or Amazon Music.

Subscribe to Hello World today to ensure you never miss a podcast episode or issue of the magazine.

Website: LINK