Schlagwort: game-development

-

More Unity: Dive deeper into 3D worlds, game design and programming

Reading Time: 4 minutesOur ‘Intro to Unity’ educational project path is a big success, sparking lots of young people’s passion for 3D game design and programming. Today we introduce the ‘More Unity‘ project path — the perfect next step for young people who have completed our ‘Intro to Unity‘ path. This new free path is…

-

Create 3D worlds with code on our first-ever Unity livestream

Reading Time: 4 minutesWe are super excited to host a livestream to introduce young coders to creating 3D worlds with Unity. Tune in at 18:30 GMT on Thursday 24 March 2022 on YouTube to find out all about our free online learning path for getting started with Unity. If you know young coders who love…

-

New free resources for young people to create 3D worlds with code in Unity

Reading Time: 4 minutesToday we’re releasing an exciting new path of projects for young people who want to create 3D worlds, stories, and games. We’ve partnered with Unity to offer any young person, anywhere, the opportunity to take their first steps in creating virtual worlds using real-time 3D. The Unity Charitable Fund, a fund of…

-

Design game graphics with Digital Making at Home

Reading Time: < 1 minute[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehpeIuMlfvc?feature=oembed&w=500&h=281] Join us for Digital Making at Home: this week, young people can explore the graphics side of video game design! Through Digital Making at Home, we invite kids all over the world to code along with us and our new videos every week. So get ready to design video…

-

Code retro games with Digital Making at Home

Reading Time: < 1 minute[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r–6fucA4ds?feature=oembed&w=500&h=281] Join us for Digital Making at Home: this week, young people can recreate classic* video games with us! Through Digital Making at Home, we invite kids all over the world to code along with us and our new videos every week. So get ready to code some classic retro…

-

Digital Making at Home: Making games

Reading Time: 4 minutesWhen you’re part of the Raspberry Pi Foundation community, you’re a part of a global family of young creators who bring things to life with the power of digital making. We imagine that, given the current changes we’re all navigating, there are probably more of you who are interested in creating new…

-

Worlds Collide – A Santa Monica Studio Limited Podcast Miniseries

Reading Time: 2 minutesIf you watched our full-length documentary, Raising Kratos, you got a glimpse into our journey reinventing the God of War franchise. It should be no surprise, we have plenty of intriguing, untold stories left to tell that dig deeper into the development of God of War. Thus, we’re proud to announce in…

-

Worlds Collide – A Santa Monica Studio Limited Podcast Miniseries

Reading Time: 2 minutesIf you watched our full-length documentary, Raising Kratos, you got a glimpse into our journey reinventing the God of War franchise. It should be no surprise, we have plenty of intriguing, untold stories left to tell that dig deeper into the development of God of War. Thus, we’re proud to announce in…

-

Worlds Collide – A Santa Monica Studio Limited Podcast Miniseries

Reading Time: 2 minutesIf you watched our full-length documentary, Raising Kratos, you got a glimpse into our journey reinventing the God of War franchise. It should be no surprise, we have plenty of intriguing, untold stories left to tell that dig deeper into the development of God of War. Thus, we’re proud to announce in…

-

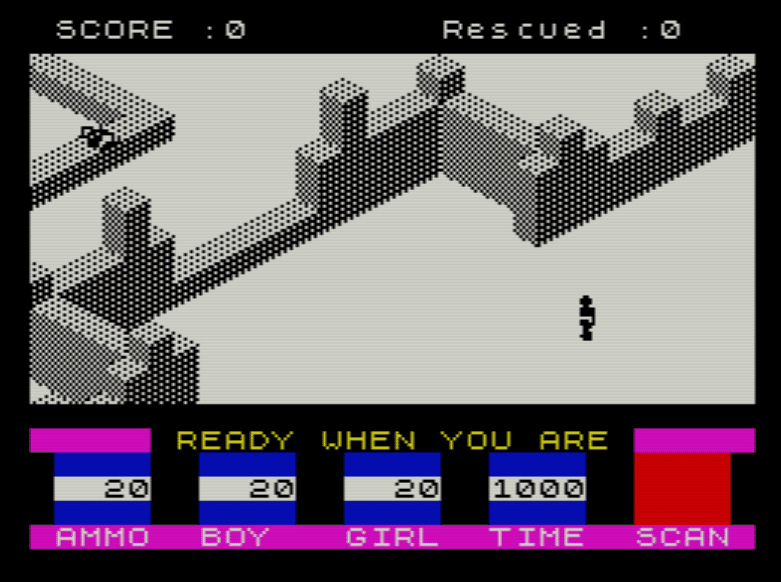

Coding an isometric game map | Wireframe issue 15

Reading Time: 4 minutesIsometric graphics give 2D games the illusion of depth. Mark Vanstone explains how to make an isometric game map of your own. Published by Quicksilva in 1983, Ant Attack was one of the earliest games to use isometric graphics. And you threw grenades at giant ants. It was brilliant. Isometric projection Most…

-

How musical game worlds are made | Wireframe #8

Reading Time: 5 minutes88 Heroes composer Mike Clark explains how music and sound intertwine to create atmospheric game worlds in this excerpt from Wireframe issue 8, available now. Music for video games is often underappreciated. When I first started writing music in my bedroom, it took me a while to realise how much I was…

-

Inside the Dreamcast homebrew scene | Wireframe issue 7

Reading Time: 4 minutesDespite its apparent death 17 years ago, the Sega Dreamcast still has a hardcore group of developers behind it. We uncover their stories in this excerpt from Wireframe issue 7, available now. In 1998, the release of the Dreamcast gave Sega an opportunity to turn around its fortunes in the home console…

-

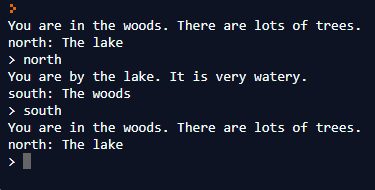

Building a text adventure | Wireframe #6

Reading Time: 5 minutesGame developer Andrew Gillett explains how to make a simple text adventure in Python — and what pitfalls to avoid while doing so — in the latest issue of Wireframe magazine, out now. Writing games in BASIC The first game I ever wrote was named Pooh. It had nothing to do with…

-

From Wireframe issue 5: Breakthrough Brits in conversation

Reading Time: 5 minutesBAFTA-recognised developers Adrienne Law and Harry Nesbitt share their thoughts on making games, work-life balance, and more in this excerpt from Wireframe issue 5, available from today. It’s certainly ‘woollies and scarf’ weather now, but the low-hanging sun provides a beautiful backdrop as Adrienne and Harry make their daily short walk from home…

-

From Wireframe issue 4: Recovering Destiny’s long-lost soundtrack

Reading Time: 5 minutesMissing for five years, Destiny’s soundtrack album, Music of the Spheres, resurfaced in 2017. Composer Marty O’Donnell reflects on what happened, in this excerpt from Wireframe issue 4, available tomorrow, 20 December. When Bungie unveiled its space-opera shooter Destiny in February 2013, it marked the end of two years of near silence…

-

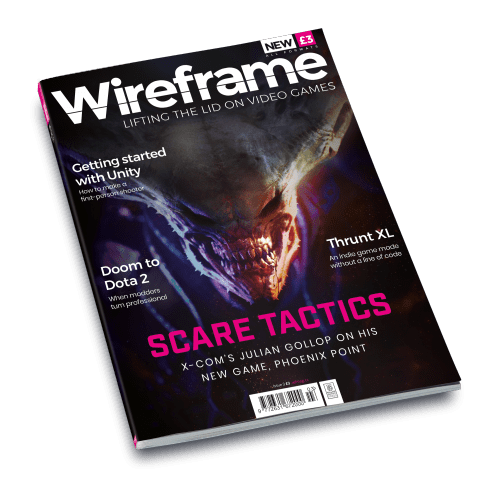

Wireframe 3: Phoenix Point, modders going pro, and more

Reading Time: 3 minutesWe said we’d be back with more, so here we are back with more: issue 3 of Wireframe, the magazine that lifts the lid on video games. From the ashes Our third issue sees the now-established mix of great features, guides, reviews, and plenty more beyond that. Headlining it all is our…

-

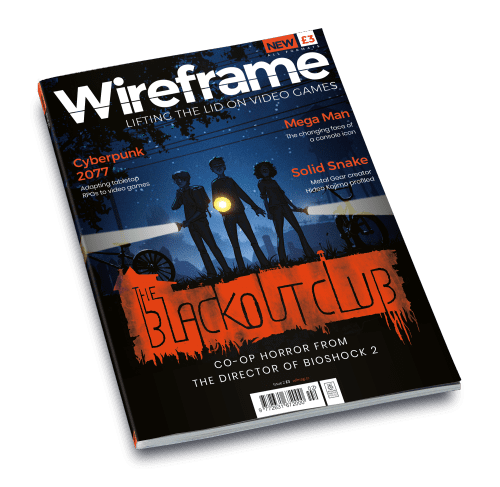

Wireframe 2: The Blackout Club, Battlefield V anxiety, and more

Reading Time: 3 minutesMomentum firmly established, we’re back with our brilliant second issue of Wireframe — the magazine that lifts the lid on video games. And yes, we are continuing to write ‘video games’ as two words. Blacking out In our sophomore edition, you’ll discover all manner of great features, guides, reviews, and everything else…

-

Wireframe issue 1 is out now!

Reading Time: 2 minutesWireframe is our new twice-monthly magazine that lifts the lid on video games. In Wireframe, we look at how games are made, who makes them, and how you can make games of your own. And today, we’re releasing our very first issue! Wireframe: the new magazine that lifts the lid on video…

-

Introducing analytics for game developers

Reading Time: 3 minutesAs a game developer, we know it’s crucial for you to understand how your game is performing on Twitch in order to create the most engaging experiences for your community. We’ve heard you ask for insights on how to better integrate with Twitch, make your game more streamable, and encourage more creators…