For our seminar series on cross-disciplinary computing, it was a delight to host Genevieve Smith-Nunes this September. Her research work involving ballet and augmented reality was a perfect fit for our theme.

Genevieve has a background in classical ballet and was also a computing teacher for several years before starting Ready Salted Code, an educational initiative around data-driven dance. She is now coming to the end of her doctoral studies at the University of Cambridge, in which she focuses on raising awareness of data ethics using ballet and brainwave data as narrative tools, working with student Computing teachers.

Why dance and computing?

You may be surprised that there are links between dance, particularly ballet, and computing. Genevieve explained that classical ballet has a strict repetitive routine, using rule-based choreography and algorithms. Her work on data-driven dance had started at the time of the announcement of the new Computing curriculum in England, when she realised the lack of gender balance in her computing classroom. As an expert in both ballet and computing, she was driven by a desire to share the more creative elements of computing with her learners.

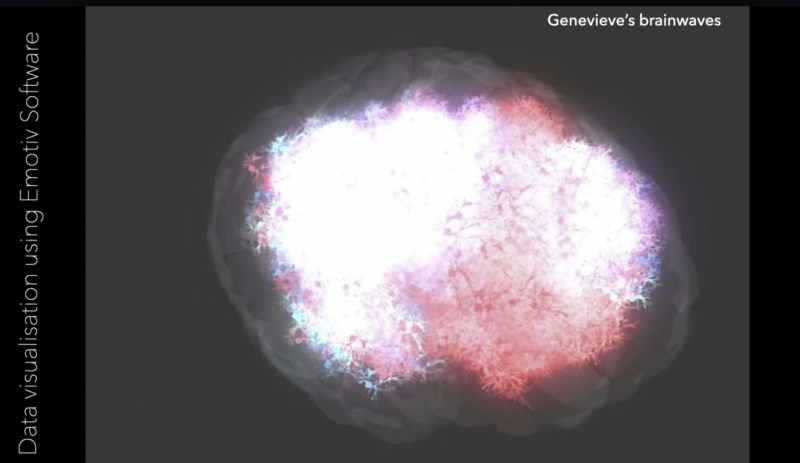

Genevieve has been working with a technologist and a choreographer for several years to develop ballets that generate biometric data and include visualisation of such data — hence her term ‘data-driven dance’. This has led to her developing a second focus in her PhD work on how Computing students can discuss questions of ethics based on the kind of biometric and brainwave data that Genevieve is collecting in her research. Students need to learn about the ethical issues surrounding data as part of their Computing studies, and Genevieve has been working with student teachers to explore ways in which her research can be used to give examples of data ethics issues in the Computing curriculum.

Collecting data during dances

Throughout her talk, Genevieve described several examples of dances she had created. One example was [arra]stre, a project that involved a live performance of a dance, plus a series of workshops breaking down the computer science theory behind the performance, including data visualisation, wearable technology, and images triggered by the dancers’ data.

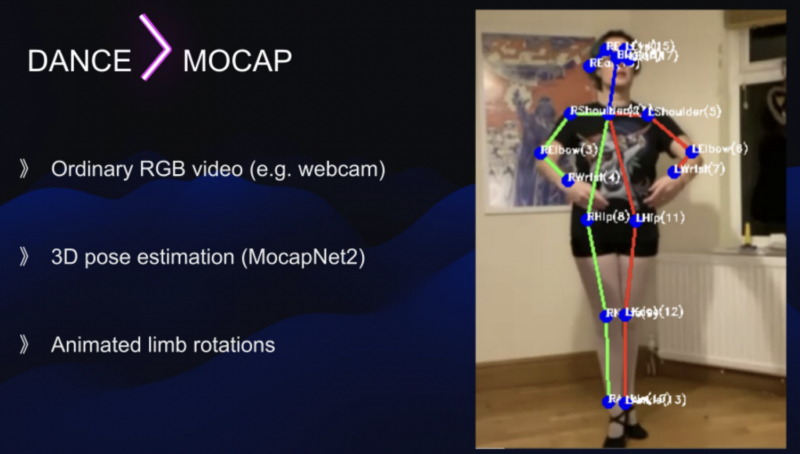

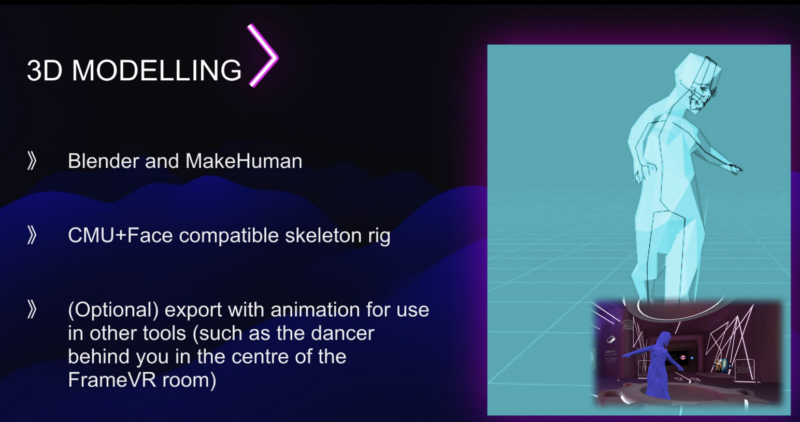

Much of Genevieve’s seminar was focused on the technologies used to capture movement data from the dancers and the challenges this involves. For example, some existing biometric tools don’t capture foot movement — which is crucial in dance — and also can’t capture movements when dancers are in the air. For some of Genevieve’s projects, dancers also wear headsets that allow collection of brainwave data.

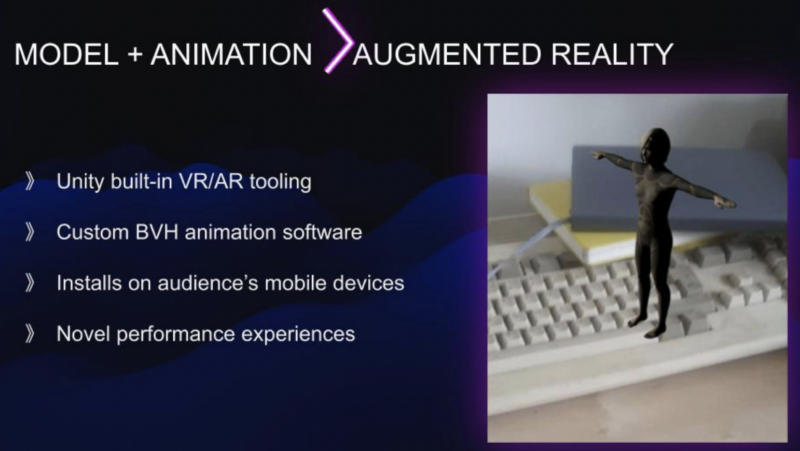

Due to interruptions to her research design caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, much of Genevieve’s PhD research took place online via video calls. New tools had to be created to capture dance performances within a digital online setting. Her research uses webcams and mobile phones to record the biometric data of dancers at 60 frames per second. A number of processes are then followed to create a digital representation of the dance: isolating the dancer in the raw video; tracking the skeleton data; using post pose estimation machine learning algorithms; and using additional software to map the joints to the correct place and rotation.

Are your brainwaves personal data?

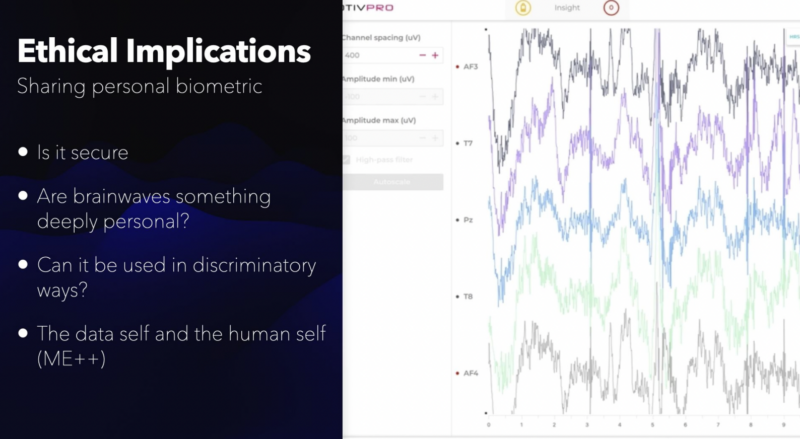

It’s clear from Genevieve’s research that she is collecting a lot of data from her research participants, particularly the dancers. The projects include collecting both biometric data and brainwave data. Ethical issues tied to brainwave data are part of the field of neuroethics, which comprises the ethical questions raised by our increasing understanding of the biology of the human brain.

Teaching learners to be mindful about how to work with personal data is at the core of the work that Genevieve is doing now. She mentioned that there are a number of ethics frameworks that can be used in this area, and highlighted the UK government’s Data Ethics Framework as being particularly straightforward with its three guiding principles of transparency, accountability, and fairness. Frameworks such as this can help to guide a classroom discussion around the security of the data, and whether the data can be used in discriminatory ways.

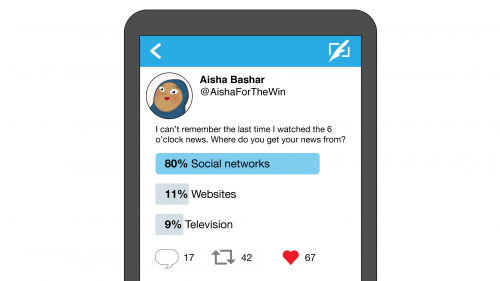

Data ethics provides lots of material for discussion in Computing classrooms. To exemplify this, Genevieve recorded her own brainwaves during dance, research, and rest activities, and then shared the data during workshops with student computing teachers. In our seminar Genevieve showed two visualisations of her own brainwave data (see the images above) and discussed how the student computing teachers in her workshops had felt that one was more “personal” than the other. The same brainwave data can be presented as a spreadsheet, or a moving graph, or an image. Student computing teachers felt that the graph data (shown above) felt more medical, and more like permanent personal data than the visualisation (shown above), but that the actual raw spreadsheet data felt the most personal and intrusive.

Watch the recording of Genevieve’s seminar to see her full talk:

You can also access her slides and the links she shared in her talk.

More to explore

There are a variety of online tools you can use to explore augmented reality: for example try out Posenet with the camera of your device.

Genevieve’s seminar used the title ME++, which refers to the data self and the human self: both are important and of equal value. Genevieve’s use of this term is inspired by William J. Mitchell’s book Me++: The Cyborg Self and the Networked City. Within his framing, the I in the digital world is more than the I of the physical world and highlights the posthuman boundary-blurring of the human and non-human.

Genevieve’s work is also inspired by Luciani Floridi’s philosophical work, and his book Ethics of Information might be something you want to investigate further. You can also read ME++ Data Ethics of Biometrics Through Ballet and AR, a paper by Genevieve about her doctoral work

Join our next seminar

In our final two seminars for this year we are exploring further aspects of cross-disciplinary computing. Just this week, Conrad Wolfram of Wolfram Technologies joined us to present his ideas on maths and a core computational curriculum. We will share a summary and recording of his talk soon.

On 2 November, Tracy Gardner and Rebecca Franks from our team will close out this series by presenting work we have been doing on computing education in non-formal settings. Sign up now to join us for this session:

We will shortly be announcing the theme of a brand-new series of seminars starting in January 2023.

Website: LINK