Schlagwort: Coronavirus

-

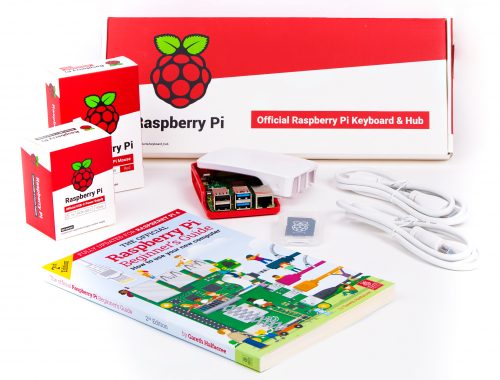

Distributing Raspberry Pi computers to help families access education

Reading Time: 4 minutesThe closure of schools has called attention to the digital divide, which sees poorer families struggling or unable to access education*. The coronavirus pandemic didn’t cause this divide, but it has highlighted it and its impact on many people in our society. As our Foundation CEO Philip outlined back in April, part…

-

What are the effects of the pandemic on education? | Hello World #13

Reading Time: 3 minutesHow has computing education changed over the last few months? And how will the coronavirus pandemic affect education in the long term? In the introduction to our newest issue of Hello World, our CEO Philip Colligan reflects on the incredible work of front-line educators, and on the challenges educators and students will…

-

Help medical research with folding@home

Reading Time: 3 minutesDid you know: the first machine to break the exaflop barrier (one quintillion floating‑point operations per second) wasn’t a huge dedicated IBM supercomputer, but a bunch of interconnected PCs with ordinary CPUs and gaming GPUs. With that in mind, welcome to the [email protected] project, which is targeting its enormous power at COVID-19…

-

Making the best of it: online learning and remote teaching

Reading Time: 7 minutesAs many educators across the world are currently faced with implementing some form of remote teaching during school closures, we thought this topic was ideal for the very first of our seminar series about computing education research. Research into online learning and remote teaching At the Raspberry Pi Foundation, we are hosting…